Introduction

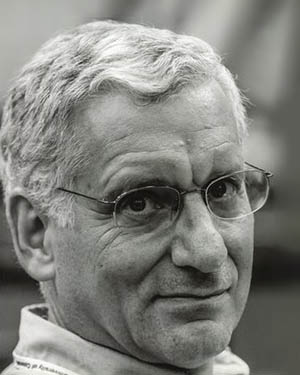

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was the first of the three great ‘classical’ utilitarian philosophers. (His successors were John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick.) He wrote on a variety of subjects, but his main interests were political and legal. Once he had arrived at the conviction that utilitarianism is true in his early twenties, Bentham’s central goal was to design a set of legal and political institutions that would conform to the ‘principle of utility’, as he called it; that is, these institutions would help to produce the most happiness.

The earliest attempt that Bentham made in this direction is partly embodied in his famous work, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, published in 1789. (I’ll refer to it as ‘IPML’.) His original goal in writing this book was to introduce a utilitarian code of criminal law, which was meant to follow in the same volume. (Bentham speaks of ‘penal’ law, not ‘criminal’.) IPML was part of a project of applied ethics: the principle of utility was to be applied to the task of designing a branch of the legal system. This task would be completed by the code, which, for various reasons, Bentham never published. While he states on the first page of IPML that his goal had been to introduce a penal code, scholars have rarely investigated how the book relates to the code of criminal law it was to introduce.

This article presents a survey of IPML and discusses Bentham’s thinking about what utilitarian criminal law would look like.1 In the first section, I describe the structure and doctrines in IPML, focusing on their relation to criminal law. In the second section, I explain what IPML suggests the basic features of a utilitarian code of criminal law would be. I conclude by discussing the manuscripts we have of the code, and one interesting section on ‘cruelty to animals’.

IPML and Utilitarian Criminal Law

Part 1: Bentham’s Moral Assumptions

IPML contains four parts. In the first, Bentham explains the fundamental moral assumptions he accepts and how he proposes to establish their truth. He accepted the form of utilitarianism now called ‘act utilitarianism’. It asserts that the morally right action for a person to perform at a given time is the one that, among her options then, produces the most happiness. A wrong act is one that produces less than the most happiness that it is possible for her to produce at that time. In IPML, Bentham speaks of acts that fail to produce the most happiness as ‘mischievous’, a central term in the book.

Bentham’s philosophical account of right action (and thus mischief) is based on what we now call a hedonistic theory of intrinsic value.2 There are two main kinds of intrinsic value: intrinsic goodness and intrinsic badness. Bentham accepted these two claims.

(i) The only thing that is intrinsically good is pleasure;

(ii) The only thing that is intrinsically bad is pain.

To say that pleasure is intrinsically good is to say that the occurrence of a pleasure has goodness in itself, or independently of any effects it may have. Likewise, to say that pain is intrinsically bad is to say that the occurrence of a pain has badness in itself, or independently of any effects it may have.

Many other things besides pleasure (like wealth and health) are good, Bentham believed, but not intrinsically good. Their goodness is, we say, ‘instrumental’. That is, they are good because they tend to produce pleasure; or because they tend to reduce pain or prevent its occurrence. Many other things besides pain (like poverty and illness) are bad, he believed, but not intrinsically bad. They are instrumentally bad: they tend to produce pain; or they tend to reduce pleasure or prevent its occurrence.

Happiness, Bentham thought, consisted in a life containing much pleasure and little pain. Now, I’ve said that Bentham’s act utilitarianism asserts that the right act for an agent to choose is the one that would produce the most happiness. But, given Bentham’s theory of intrinsic value, he could also have said that a right act would have the best results, that is, would produce the most intrinsic value. So, I’ll say a little more about Bentham’s thinking about intrinsic value. We might restate it by saying that pain is a social or moral cost, and the more of it that an act causes, the worse the result is; pleasure is a social benefit, and the more of it that an act causes, the better the result is. An act might be right, Bentham thought, if it causes some pain, so long as it also causes enough pleasure, but it always would be better if the pleasure could be caused with less pain. Bentham believed that sometimes punishment is right, which is to say that sometimes the painfulness of a punishment is sufficiently outweighed by the pleasure it causes or the pain it prevents. I’ll return to this last statement shortly.

In a powerful passage in a book related to IPML, Bentham emphasized that utilitarian calculations take into account the pleasures and pains of both victims and offenders (or ‘delinquents’).

It ought not to be forgotten, although it has been frequently forgotten, that the delinquent is a member of the community, as well as any other individual—as well as the party injured himself; and that there is just as much reason for consulting his interest as that of any other. His welfare is proportionably the welfare of the community—his suffering the suffering of the community. It may be right that the interest of the delinquent should in part be sacrificed to that of the rest of the community; but it never can be right that it should be totally disregarded.3

This passage has important implications for current debates, for example, about ‘mass incarceration’ in the US and elsewhere. It has been plausibly argued that the harsh criminal justice policies in places like the US have been based in part on the assumption that the suffering of criminals “doesn’t count”, or counts less, than the suffering of others.4

Bentham didn’t think that any utilitarian lawmaker in his day could carry out calculations of the instrumental value of actions in precise amounts. Yet, he believed that reasonable estimates could often be made, since the negative value of acts like killing or stealing could at least be estimated.

In IPML, Bentham states and defends his general philosophical claims, such as hedonism, but he tends then to focus on the issues that would particularly concern a utilitarian legislator. The purpose of a system of utilitarian criminal law, roughly speaking, would be to reduce the amount of wrongdoing or, in Bentham’s terminology, the number of mischievous acts.5 If a legal system reduces the number of mischievous acts, it would be likely to increase the amount of happiness in society and, thereby, the amount of intrinsic value.

Part 2: Bentham’s Psychological Theories

The second part of IPML consists largely of psychological material. Some of it describes the different kinds of pleasures and pains, as well as the great variety of factors that influence whether a given act will cause a person to feel pleasure or pain. This information would be useful in determining whether a given act was particularly mischievous, say, because the victim was a child or disabled. It would also be useful in determining the appropriate punishment for a convicted offender since, Bentham says, it is desirable that the system of punishments be ‘equable’.6 That is, if a legislator tries to impose a certain amount of pain on different offenders, the punishments chosen should have the same effect. But a fine of, say, $500 might produce more pain for a poor criminal who commits a certain offense than for a wealthier one, so this fine would be ‘inequable’.

Six chapters in IPML describe and explain human actions. The topics include motives, intentions, and the consequences of actions. Bentham treats human decision-making as a causal process that can be understood by intelligent and well-informed observers and affected by legal and social practices. The topics remain important in thinking about criminal law. For example, legal systems generally punish individuals who produce harm intentionally more severely than individuals who produce it unintentionally. In chapter 12 of IPML, Bentham discusses why a utilitarian criminal code would do so. He argues that intentionally-inflicted harm tends to cause more fear in the public.

Scholars have debated what position Bentham took about the ultimate goals or ends of human actions. Sidgwick claimed that Bentham accepted psychological hedonism: the theory that every person is always trying to produce the most happiness for herself when she acts.7 If psychological hedonism is true, then people might sometimes try to produce happiness for other people, but they would only do this if they believed it to be the best means of promoting their own happiness. I think that in IPML Bentham’s position is that people generally act in order to produce happiness for themselves, but not always. He believed that people sometimes act from sympathy or benevolence, taking the happiness of others as their goal. They also sometimes act from ill will or malice, taking the pain or unhappiness of others as their goal.

Part 3: The Severity of Punishment

The third part of IPML brings together Bentham’s moral principles and his psychological theories and addresses the issue of how severely convicted offenders should be punished. (He uses a familiar way of describing the issue and speaks of the ‘proportion’ of punishments and crimes.) The basic strategy of crime reduction that Bentham endorses is what we call ‘deterrence’: the law announces that offenders will be punished, which tends to alter potential offenders’ decision-making. When punishments are well-designed, potential offenders will choose not to risk undergoing them, and the mischief they would have produced is averted. Thus, deterrence has instrumental value by preventing painful (or pleasure-reducing) events from occurring.

Bentham understands that for deterrence to work, punishments need not only to be announced, but also carried out when a person breaks the law. A system of deterrent punishments threatens potential offenders with painful consequences if they offend; and it carries out the threat if they are found to have done so. Ideally, the threats would be perfectly designed and no one would ever break the law. In practice, punishments sometimes need to be imposed.

Bentham refines both his psychological and moral assumptions in discussing deterrence. On the psychological side, he notes that people do not simply do what they believe will produce the most happiness for themselves or others. Two other psychological factors affect their decision-making.

The first is their beliefs about the probability of achieving their ends. This means that a potential offender might act in a way that she believes has a high probability of success but will only have a small ‘payoff’. For example, a potential thief might choose to steal a wallet rather than rob a bank because she believes that she has a much better chance of succeeding in the former case than in the latter. On the other hand, she might prefer a small chance of a large reward. But in either case her beliefs about the probability of success shape her decision-making.

The second psychological factor that affects decision-making is what Bentham calls ‘proximity’, by which he means ‘proximity in time’. He thinks that beliefs about the timing of a pleasure or pain can have an independent effect on a person’s decisions. For example, if a potential offender believes that one act has a 50% chance of producing an intense pleasure tomorrow, she may be more inclined to choose it rather than another act that she believes has a 60% chance of producing such a pleasure six months from now. Likewise, she might prefer a 60% chance of an intense pain six months from now, over a 50% chance of a similar pain tomorrow. This psychological phenomenon is now usually called ‘discounting the future’ and has been experimentally demonstrated.

The role of discounting and probability in the decision-making of potential offenders is important because the rewards of criminal activity often closely follow the offense, while the pains of punishment can have a low probability and come much later. Bentham thought that when potential offenders have these beliefs and attitudes, the severity of the threatened punishment must be increased for deterrence to occur.8

Bentham also refines the moral claims he made earlier in the book. I stated above that the purpose of a system of utilitarian criminal law, roughly speaking, would be to reduce the amount of wrongdoing or the number of mischievous acts. However, utilitarianism places restrictions on how severe or lenient deterrent punishments can be. That is, even if a punishment reduces the amount of wrongdoing by deterring potential offenders, utilitarianism might nonetheless entail that such a punishment is wrong. It might be wrong in two different ways. It might be too lenient: if it had been more severe, it would have prevented more wrongdoing and thereby produced more overall happiness. On the other hand, it might be too severe: if it had been more lenient, it would have thereby produced more overall happiness.

You might doubt that overseverity is a possibility, given Bentham’s utilitarianism. While some of his statements in IPML could be interpreted differently,9 Bentham’s position is that some deterrent punishments would be too severe, and he calls such punishments ‘unprofitable’. For such a punishment, the mischief it “would produce would be greater than what it prevented”.10

Consider an act utilitarian judge who decides the proper severity of a convicted criminal’s punishment. In theory, such a judge would seek to determine which severity level would produce the most overall happiness for everyone in society (including the criminal). In IPML, Bentham focuses on two effects of punishment: the pain experienced by the punished criminal, and averting the pain of possible future crime victims. He discusses a number of rules to help a utilitarian judge make sentencing decisions. For example, offenses that cause more mischief call for more severe punishments. Consequently, other things being equal, the punishment for murder should be greater than the punishment for stealing a car. This is because the loss of a person’s life generally represents a greater reduction in the amount of happiness in society than the loss of the use of her car.

A utilitarian judge needs to consider not only how much mischief a given sort of offense causes, but also how many offenses punishments of different severity levels would prevent. Suppose that Joe is convicted of stealing a car, and one option is to punish him with one year in prison. This could deter Joe and others from offending. Let’s suppose that Joe would steal two cars if he were not punished this severely. (The deterrent effect of a punishment on the punished person is called ‘specific deterrence’, while the effects of punishment on society at large is called ‘general deterrence’.) Suppose also that Joe’s punishment would deter two people who know him from each stealing one car. As we say: Joe’s punishment would serve as an ‘example’ to them and deter them, too, from offending. (An example of general deterrence.) Overall, punishing Joe with one year in prison would thus prevent four car thefts.

A utilitarian judge also needs to consider whether a more or less severe punishment for Joe would produce more overall happiness (or intrinsic value). Consider the effects of greater severity, such as by doubling the amount of pain that Joe will undergo. This might mean extending his prison sentence from one to three years. (Merely doubling his prison term from one to two years might not double his pain, because the worst year in prison might well be the first, as Joe might get used to prison over time.) Now suppose that imprisoning Joe for three years would deter five car thefts. In this case, doubling the punishment severity would not double its deterrent effect. This could be true because, for example, no other potential car thieves learn of Joe’s punishment. In this scenario, then it might be true that doubling the severity of Joe’s punishment would not produce the most happiness.

To settle this question, Bentham would ask us to compare the effects of the two punishments on the amount of happiness (or intrinsic value) in society at large. It is plausible that the amount of Joe’s added pain in a three-year prison sentence would be greater than the amount of happiness that the fifth potential victim would have if she kept her car. If so, there would be more happiness in society overall if Joe were punished with one year in prison and four car thefts were prevented, than if Joe were punished with three years in prison and five car thefts were prevented. The reverse is also possible, if the fifth potential victim would suffer more from the loss of her car than Joe would suffer from the extra two years’ imprisonment.

Of course, a third option might produce the most happiness. So, utilitarianism would ideally require consideration of all other options and all other effects the punishment would have on the happiness of people: for example, the various options’ costs to taxpayers, and the effects on the families of victims and criminals. Critically, utilitarian judges would need to have at least approximate numerical values for the amounts of pleasure and pain involved in being in prison and losing one’s car, as well as for the deterrence that various punishments achieve. In Bentham’s day numerical precision on such matters was a distant ideal; the best that could be done was rough estimates. The social sciences of criminology, economics and psychology have made great progress since.11

But Bentham’s central moral claims can take account of these considerations. To repeat, his key claims are that (i) a judge ought to impose the punishment whose severity would produce the most overall happiness (or intrinsic value), and (ii) punishments that are more severe than that would be wrong, even if they deterred more offenses. Such punishments would be ‘unprofitable’, in the sense that the social costs of increased severity would exceed the extra social benefits in crime reduction.

Part 4: Making Acts into Offenses

The longest chapter in IPML, “Division of Offenses”, presents an elaborate classification of possible offenses. I’ll briefly explain the basic features of the scheme, and then discuss its relevance to Bentham’s project of designing a system of utilitarian criminal law.

Bentham’s four main categories of possible offenses are (i) private offenses; (ii) semi-public offenses; (iii) self-regarding offenses and (iv) public offenses. The categories correspond to different types of mischief and how they are caused.

Private offenses involve one person causing mischief to one or more other identifiable persons. The mischief may be inflicted on the other person’s body (as in a physical assault), or on her mind (as with threats of violence or harassment). Other sorts of mischief involve damaging or stealing a person’s property or damaging her reputation, for example, by falsely asserting that she has criminal convictions. Private offenses include the most familiar sorts of crimes: murder, rape, theft and burglary.

Semi-public offenses pose risks of mischief to limited groups of people. They include careless acts like failing to handle explosives safely, as well as knowingly imposing risk by, say, selling ineffective medicines.

A self-regarding offense involves causing mischief to one’s self, and is the most interesting of the four categories. Bentham expresses great skepticism about whether many of the supposedly self-regarding offenses then recognized in England and elsewhere truly caused mischief to the individuals performing them. He’s skeptical because he believes that people generally know what gives them pleasure. So, if legislators prohibit an action on the grounds that it harms the persons performing it, the chances are good that the legislators are mistaken, and it does not actually harm them. Bentham mentions suicide, drunkenness, and gambling, among other types of actions, as examples of possible self-regarding offenses. In manuscripts unpublished in his lifetime, he argued that consenting same-sex sexual relations should not be an offense.12 In Bentham’s time English law punished such acts with death. More generally, his skeptical isolation of a category of acts allegedly harming the people who perform them was pathbreaking, and surely influenced John Stuart Mill’s famous work on this issue, On Liberty.13

Public offenses involve acts that pose risks of mischief to the entire society. Bentham focuses on acts that affect the operations of government, including tax evasion, bribery of public officials, and treason.

IPML’s final chapter contains two sections and states that three more are to follow. They do not, however, and the book breaks off after the second section. The penal code might have followed the fifth section.

A Utilitarian Penal Code

I’ve now summarized the main theoretical materials in IPML that Bentham thought he needed to design a utilitarian penal code. However, the book does not carry out the three main tasks that would have completed his project. These are: (i) determining which of the many possible offenses should actually be legally prohibited; (ii) giving precise legal definitions of these offenses; and (iii) specifying the punishments to be imposed on offenders. I’ll say something about each task, as Bentham understood them.

IPML suggests that a utilitarian approach to determining whether a type of act, described in “Division of Offenses”, should be made into an offense would involve at least two steps. First, it would be necessary to determine if that type of act generally caused mischief. This would be straightforward, Bentham thought, for an act like killing. But it wouldn’t be straightforward for an act like tax evasion, whose mischief is subtle and sometimes uncertain. Finally, Bentham suggests, as I mentioned, that many self-regarding acts which were often treated as offenses in his time, might not cause mischief at all. So, their analysis would require great care.

The second step concerns acts that are found to be generally mischievous. It is then necessary to determine whether punishing such acts is profitable. We saw that profitability plays a role in setting the right punishment severity level. But it would also help to determine whether a type of act should be punished at all. Bentham gives the example of punishing fornication, that is, sexual intercourse between unmarried people. He seems to grant that this sort of act is mischievous, but he says that punishing it would produce much more mischief than it would prevent. The difficulty, Bentham says, would be in procuring evidence: since the act usually occurs in private, authorities would often have to rely on family members informing on each other, which would seriously harm such families.14 Hence, fornication fails the second test and ought not to be made an offense.

Assuming that a type of act passes both utilitarian tests, it would be necessary to give a precise and clear definition of the offense. One reason for this is to better achieve deterrence. People are more likely to refrain from committing acts that they know are prohibited. A related point is that even if a type of act is generally mischievous, there may be instances of it that are not. Bentham says that “in some circumstances even to kill a man may be a [socially] beneficial act”.15 Utilitarianism would generally favor making an exception to the prohibition on killing in such cases (for instance, in self defense), and they, too, should be clearly stated.

Finally, Bentham’s code would need to specify what the punishments would be for each offense, in order to achieve the optimal level of deterrence. The threats of punishment would be designed to deter most, if not all, potential offenders, and they would therefore need to be clearly specified. IPML suggests that judges would be given some discretion in setting the severity of punishments, presumably in part because different people would pose different risks of reoffending. This means that the code would need to state the range of possible punishments for a given offense, and presumably give judges guidance on what specific punishments in the range to impose on various offenders.

One Section in Bentham’s Penal Code Manuscripts: ‘Cruelty to Animals’

Fortunately, we have evidence about how Bentham’s penal code would have carried out the three tasks mentioned above. For one thing, Bentham eventually published works that were written around the time he wrote most of IPML (1777-80), and these address some issues concerning the design of a system of criminal law. One important such work is The Rationale of Punishment, which was published in 1830; it contains parts written around 1778 that discuss the advantages and disadvantages of various kinds of punishment, such as corporal punishment and imprisonment.

However, the main evidence we have are the voluminous manuscripts of the penal code. While they haven’t been published, the remarkable Transcribe Bentham project has made virtually all of them available online. Transcribe Bentham is a venture in crowdsourcing: volunteers examine digital images of manuscript pages and transcribe them. The images and their transcriptions are then put online. I’ve been studying the penal code manuscripts.16

To illustrate how informative these transcriptions are, I’ll discuss one interesting section in the manuscripts. It’s connected to a famous passage in IPML, which occurs in a footnote in the last chapter.17 Here Bentham states that many animals can feel pain (and presumably pleasure). He then applies the hedonistic theory of value to these experiences of animals. The pleasures and pains of animals, he says, ought to be counted in utilitarian calculations, even if they are not rational creatures—a point he doesn’t fully concede.

[S]uppose the case were otherwise [and animals are not rational], what would it avail? the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?18

Peter Singer drew attention to this passage, and rightly described it as “forward-looking”, meaning that it was far ahead of its time.19 Bentham’s focus in IPML was criminal law, and in this respect he was definitely ahead of his time. The note refers the reader to a section in the penal code on ‘cruelty to animals’, so we know that Bentham wanted to make such acts into offenses. The first modern law penalizing cruelty to certain animals was enacted in 1822 in England. Almost all countries eventually enacted such laws.

In the manuscripts we can see more of Bentham’s thinking on the three issues a penal code would need to address about cruelty to animals.20 These manuscripts are unfinished, but they give us a nice sense of Bentham’s mind at work on a fundamentally new set of philosophical and legal issues. The note to this sentence provides a link to the first page.21

Both IPML and the manuscripts assert that some animals can feel pain, so to that extent Bentham seems confident that he’s established that cruelty to animals is mischievous. He makes the further claim that there’s one kind of pain that humans can feel and animals can’t, namely, the pains of ‘anticipation’. This means that humans can be pained to think that they will die; animals can’t have such pains. Bentham argues that killing a person tends to cause other people to have painful thoughts of the possibility of their being killed; animals don’t have such pains. He concludes that killing one animal is “nothing” to other animals: mischief only arises if an animal is tortured or vexed, not if it’s killed. On the other hand, killing one person causes pain and mischief for other persons.22

Bentham, I think, makes an error here in applying hedonism to the experiences of animals. Even if a cow, say, can’t anticipate its death, if it dies today it might be deprived of a pleasant life extending into the future. This point applies to humans, too: the main reason why a person’s death is usually bad, according to a plausible hedonistic account, is that it usually would deprive her of many possible pleasures.23

Bentham’s account of the mischief that animals can be subjected to leads him to defining cruelty to animals as being “wantonly instrumental in hurting or worrying [that is, causing fear to] any animal”.24 He explains that to act ‘wantonly’ is to deliberately cause pain for its own sake, or for no useful purpose. The useful purposes he mentions are (i) ‘chastisement’, which seems to refer to a program of training an animal; (ii) the ‘conveniences of man’, including providing us with food, clothing, and medicines; (iii) defending a person from being hurt or annoyed by an animal; (iv) serving in scientific experiments.25

If hedonism entails that the death of an animal can be instrumentally bad, in that it can deprive it of future pleasures, Bentham’s definition of the offense of cruelty to animals might need revision. This is because some acts of killing animals will also be mischievous, and thus eligible for legal prohibition. A complete utilitarian analysis of this question, I said, would also involve consideration of the profitability of punishing Bentham’s relatively narrow offense, or a wider one that included some acts of killing animals. His manuscripts don’t address the issue of profitability.

Bentham states that persons who are found guilty of the offense will be subject to “penance more or less public”, and that males below the age of 15 and of a lower social class may be whipped.26 The ‘penance’ Bentham envisioned was some sort of shaming, perhaps in a pillory if it was to be ‘public’. Bentham, like others of his day, thought that corporal punishments like whipping were inappropriate for women, because it would require exposing too much of their bodies. He also thought, as others did, that some punishments weren’t suitable for upper class individuals, since their refined sensibilities would make them inequably severe.

This sample illustrates how helpful the penal code manuscripts are in understanding Bentham’s pioneering efforts in the philosophy of criminal law, and the respects in which he was a man of his time, and those in which he was far ahead of it.

About the Author

Steve Sverdlik taught philosophy at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. He writes about the philosophy of criminal law and its history. His Bentham’s Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation: A Guide (Oxford University Press) will appear in 2023.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

I give more detail in my forthcoming book: Bentham’s Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation: A Guide (Oxford University Press). ↩︎

An excellent study of hedonism is Fred Feldman, Pleasure and the Good Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ↩︎

The Rationale of Punishment. In The Works of Jeremy Bentham. Edited by John Bowring. Edinburgh: William Tait, 1838-43. Vol. 1, p. 398. ↩︎

Mark Kleiman, When Brute Force Fails, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009. P. 30. ↩︎

This is only an approximation. It obviously wouldn’t be a good thing to replace two minor thefts with one murder. What ultimately matters, for utilitarians, is not the number of wrong or ‘mischievous’ acts but the severity of their effect on overall happiness. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 15, paragraph 3. ↩︎

Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7th edition. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1981. Pp. 41, 84. ↩︎

Later in his career Bentham realized that the law can increase the probability of punishment, which would allow it to decrease its severity. For example, he understood that a police force could increase the probability of arresting and punishing criminals. There were no police forces in England when Bentham wrote IPML. For a contemporary treatment of the role of probability and discounting in potential criminals’ decision-making, see Kleiman, When Brute Force Fails, chapter 5. ↩︎

Bentham states, in effect, that the principle of utility entails that every offender who can be deterred should be deterred. See IPML, chapter 14, paragraphs 8 and 9. But this is in tension with his earlier remarks about ‘unprofitability’ in IPML, chapter 13, paragraphs 3, 13-6. I explore this issue in “Bentham on Temptation and Deterrence” Utilitas (September 2019), and defend the interpretation presented here. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 13, paragraph 3. See also paragraphs 13-6. ↩︎

A survey of the economics and science of deterrence is Kleiman, When Brute Force Fails, chapters 2-6. ↩︎

“Offenses against One’s Self: Paederasty.” Journal of Homosexuality (Summer and Fall 1978). ↩︎

The classic contemporary treatment of ‘legal paternalism’ is Joel Feinberg, Harm to Self, New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 17, paragraph 15. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 7, paragraph 21. ↩︎

http://transcribe-bentham.ucl.ac.uk/td/Penal_Code. Boxes 71 and 72 contain the manuscripts from around 1780. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 17, paragraph 4. ↩︎

IPML, chapter 17, paragraph 4. ↩︎

Peter Singer, Animal Liberation, New York: Harper, 2009. P. 7. ↩︎

http://transcribe-bentham.ucl.ac.uk/td/JB/072/214/004. Compare IPML, chapter 17, paragraph 4. ↩︎

See Shelly Kagan’s discussion of the general ‘deprivation account’ of the badness of death. Death. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, 205-33. I’ve used a hedonistic version of this account. This applies only to the issue of why the death of an animal can be bad for the animal itself. Bentham also argues that hurting an animal can be instrumentally bad for others, by eventually causing pain to the person who hurts the animal, and to other persons. http://transcribe-bentham.ucl.ac.uk/td/JB/072/214/002-3 ↩︎