This essay was adapted (with permission) from two of Joe Carlsmith’s essays on expected utility theory— Skyscrapers and madmen and Why it can be OK to predictably lose—edited and rewritten for utilitarianism.net by Vikram Balasubramanian.

On Expected Utility

Decision theories aim to tell us how to respond to uncertainty; in particular, how to make our decisions in a coherent and consistent manner across similar situations. Expected Utility Maximization (EUM) directs us to weigh the potential value (or utility) of an outcome by its probability, yielding an expected value (or expected utility). If we take impartial welfarism to constitute the relevant values, then applying EUM as a decision theory leads us to expectational utilitarianism. But the underlying decision theory is more general, and could also be applied to other, non-utilitarian values. This essay explains Expected Utility Maximization as a decision theory and defends its most distinctive feature: that it can advise us to choose options that will predictably lose.

Intuitively, we understand that any decision comes with pros and cons, which have a certain probability of occurring. As implied by the name, EUM tells the decisionmaker to choose the decision that has the greatest expected value. We calculate the expected value by adding up the value of each decision-path and multiplying by the probability of the event occurring.

Though value and utility are contested notions, we can use the framework of EUM with any account of value. Philosophers often measure value in terms of lives saved, dollars, well-being, or just about any unit, as long as it is consistent across cases and relevant to the situation.

Suppose you are trying to decide which of two charities to donate a fixed sum to. Charity A would dispense one intensive course of treatment for a single patient, saving their life. Charity B would use the same funds to distribute an existing oral medication to 1000 people, though scientists expect that the likelihood the old treatment will work on the new strain is only 1% (assume that the medicine will work equally well or not well for every single person). So your choice is between saving one person with a 100% likelihood (A); or taking a 1% chance to save all 1000 people.

Betting on a 1% chance of success seems like a risky gamble, particularly when there are lives at stake. But while it’s more risky, supporting Charity B saves more lives in expectation—10 rather than just 1. We work out the expected utility of each option by multiplying each possible outcome’s probability with the value it would have if it occurred.1

More precisely, implementing EUM involves three things:

- Assigning probabilities to the possible outcomes of their actions.

- Assigning real-numbered “utilities” to these outcomes, representing their value or degree of preferred-ness.

- Choosing the action that yields the highest expected utility—i.e., the sum, across the action’s possible outcomes, of each outcome’s utility multiplied by its probability.

Maximal Skyscraper

We can think of EUM via a “skyscraper” model, which represents the relative likelihood of different events as the relative area in a square. The decision between charities A and B above can be represented as:

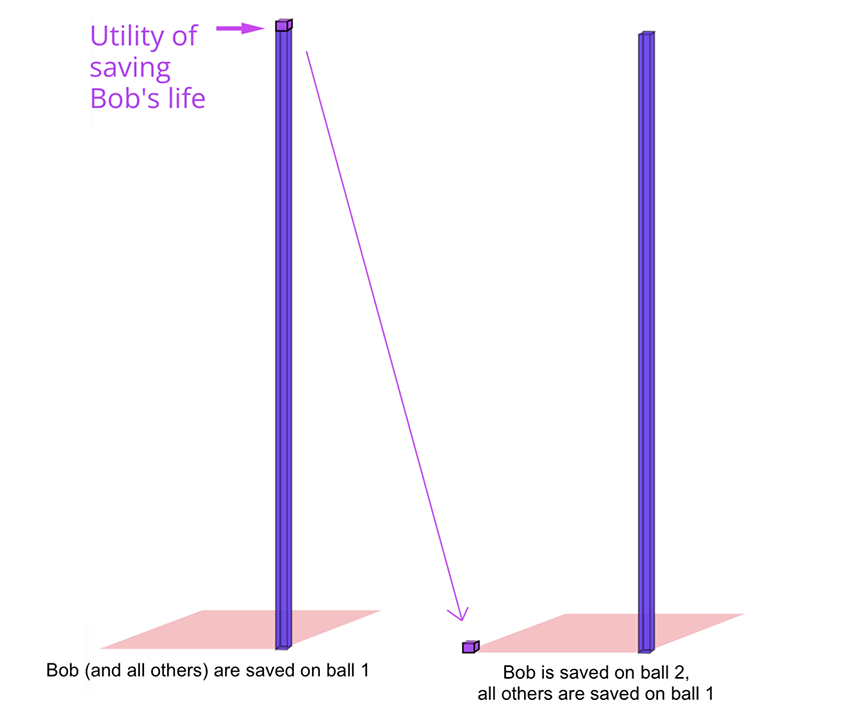

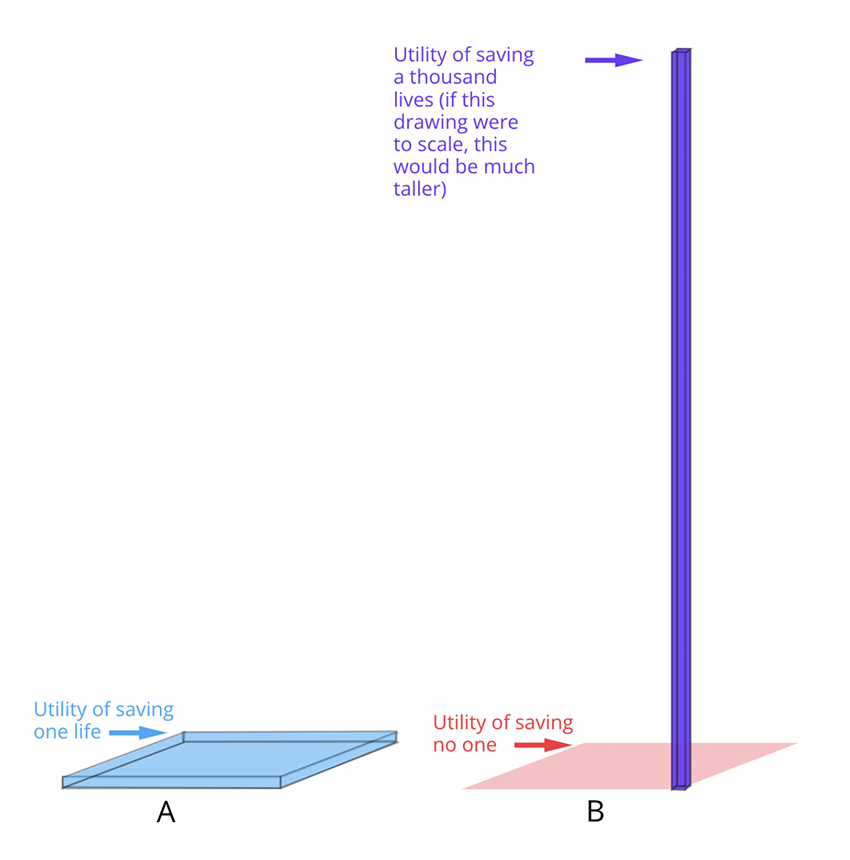

Utilities, then, behave like an extra dimension. We multiply our two-dimensional square base by a utility, which acts like “height,” to create a three-dimensional object—one that looks like a skyscraper.

In this model, possible outcomes can be represented as three-dimensional skyscrapers. The base size of each skyscraper represents its relative probability, and its height represents value: how good it would be if this outcome were realized. Each action maps to a cityscape representing the full range of possible outcomes associated with the action. According to EUM, we should choose the action with the greatest total volume in its cityscape, regardless of how condensed or dispersed a form this takes.

In the above example, A’s cityscape contains a very short skyscraper with only one floor but a large area. In contrast, B is mostly empty at base, but contains a narrow skyscraper with 1,000 floors. Since B has the greater total volume, EUM recommends B over A.

Many people intuitively pick A over B, just as I suspect many would intuitively say that city A is “bigger” than city B. In reality, the top part of skyscraper B is hidden in the clouds. The size of the benefit of B is obscured by the fact that it is too tall to get a full view of. As the number of lives in a scenario rises, we lose our ability to fully comprehend the value, well-being, and personhood of each individual. Cognitive scientists and psychologists have long observed that humans have difficulty thinking about and comparing large numbers of people, especially when large numbers of people are suffering.2 EUM tries to overcome this by checking for consistency in the beliefs between scenarios involving small and large numbers.

Our human cognitive heuristics and limitations sometimes prevent us from grasping a plain truth:3 saving ten lives is ten times more important than saving one life, all other things equal. Saving one-hundred lives is one-hundred times more important than saving one life. Thinking in skyscrapers and cityscapes helps us focus on the true size of the expected benefit of one’s choices.

Only One Shot

Still, if you choose B, to save 1,000 lives with a 1% chance, the most likely outcome is that you save no one. The expectation of choosing B is saving 10 lives (1,000 lives * 1%). But this is not the same as what you should actually expect, or regard as most likely, to happen.

If we flip a fair coin, we know that we should have a 50% chance of getting heads. Yet, if we flip the coin 10 times, it would not be unreasonable to get 6 heads and 4 tails. In fact, you would only get 5 heads 25% of the time, so most of the time you won’t get a result representing the underlying probability of the coin. But if you repeated this experiment and flipped the coin infinitely many times, 50% of your tosses will be heads. Statisticians call this taking the limit as the number of trials (tosses) approaches infinity.

However, in real-life scenarios, we can’t repeat things infinitely many times, or even just many times. In our example of saving 1,000 lives with a 1% chance, we can only choose once.

The basic argument for EUM is that it does well in the long run, but this isn’t guaranteed: sometimes failures are correlated. Recall Charity B’s oral medication: it’s not that it saves everyone in 1% of trials. Rather, there’s a 1% chance that it always works, and a 99% chance that it never does. In the latter case, people could choose B over and over, and never save anyone.

In other cases, repetition is not even an option. Consider the decision of what career to pursue if your goal is to do the most good. Sure, you can change careers, but only a limited number of times. You only have one life. One shot. And it can be difficult to get real-world feedback about the actual value of your career, so decisions to change careers often rest on ambiguous evidence.

So, you could choose to spend your life working on curing a rare genetic disease, working in finance to “earn to give”, or working for Oxfam. These all have different utilities and different probabilities of actually making a difference. You might not ever find a cure for the disease or become a successful stockbroker who can donate a lot of money.

Perhaps you may say: “Yes, but if everyone with my values follows EUM, then you get to repeat the choice across people, rather than across time.” But this isn’t enough, either.

- First, EUM favors choosing B over A, assuming B maximizes utility, even if this is the only time you can make this decision.

- Second, sometimes no one shares your values. Bob, for example, might aim to eat the maximum number of corn fritters and care little about anything else. But he stands little chance of justifying his “expected fritters-eaten-by-Bob” maximization via reference to some kind of community effort.

- Third, it is hard to get the community oriented around a single goal or decision. What happens when they won’t repeat choices?

- Fourth, sometimes failures are correlated across people, too. For example, if there’s a 5% chance that an asteroid is headed toward Earth, and everyone following EUM joins the asteroid deflection effort, then the whole community effort still has a 95% chance of being irrelevant.

So, EUM needs another argument to be justified.

Why it is OK to predictably lose

Let’s continue to use the following example throughout the next section:

Choice A: Certainly save one life.

Choice B: Save all 1,000 lives with a 1% chance.

One reason it might be right to choose B (even if you predictably lose), is because the payoff if you win is just that important. One thousand lives, while hard to conceptualize, is 1,000 times more important than one life. A career spent working to prevent existential risks—even when the probability of catastrophe is low—can be worthwhile because the future is that precious and the cost of catastrophe is that high.

It’s a hard bullet to bite, so in the next sections, we’ll provide some tools for bringing this argument into focus.

Conditional Probabilities

Low-probability events are really just more likely events conditional on other events—bigger conditional probabilities in disguise. If we think a slight gamble is worth taking over benefit X, then we should also prefer a 50% chance of getting to take the slight gamble over a 50% chance of X. A reader versed in math may notice that this is due to the linearity of expectation. But a 50% chance of getting to take a further gamble leaves us overall unlikely to win anything. Consistency forces us to tolerate this prospect.

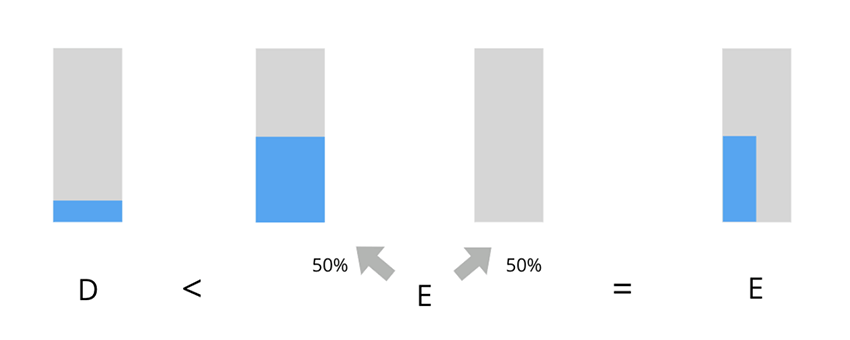

To see this, consider Case 1:

A: Certainly save one life.

C: Flip a fair coin; if it is heads, save 5 lives, tails, save 0.

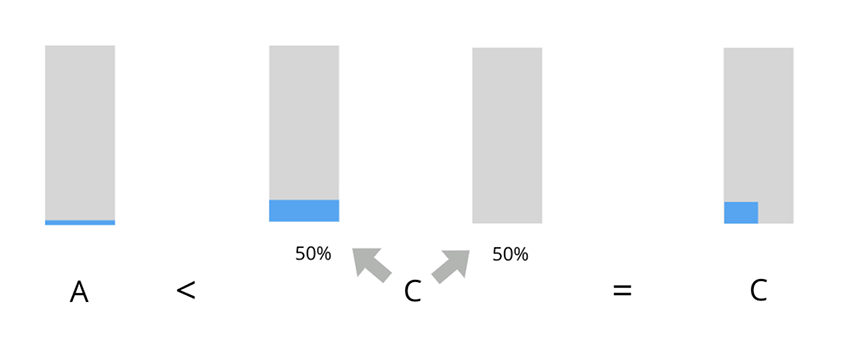

In this case, it seems intuitively plausible that we should prefer C, just as EUM recommends. Importantly, we don’t think that choosing C “predictably loses”: a 50% chance of winning represents decent odds. In the two-dimensional skyscraper diagram below, the blue-shaded area represents the expected utility of a choice and the gray-shaded area represents no utility. (Note that the composite skyscraper for C is obtained by combining the two possible outcomes, taking 50% of the weighting from each.)

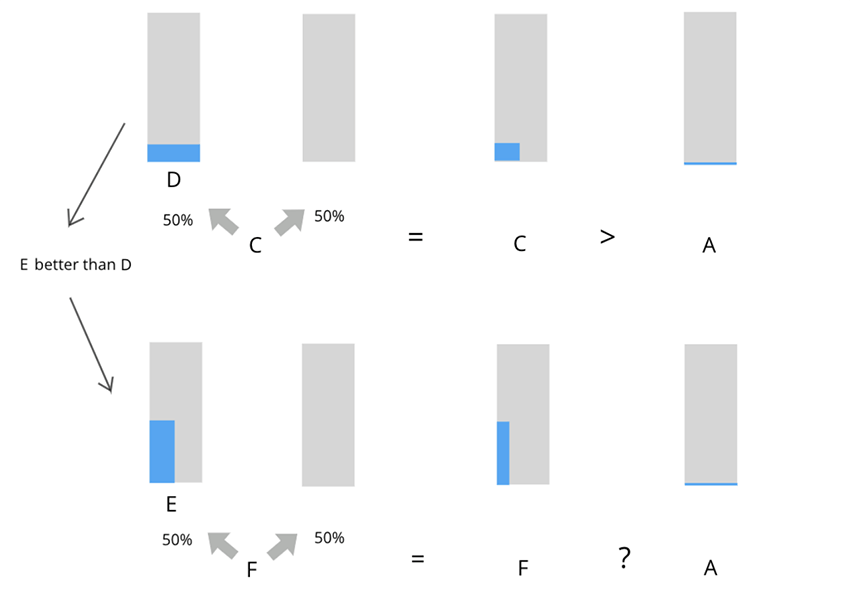

Next, consider Case 2:

D: Certainly save five lives.

E: Flip a fair coin; if it is heads, save 15 lives, tails, save 0.

As before, it seems reasonable to prefer E over D: it has greater expected value, and the chance of success—at 50%—remains tolerably high.

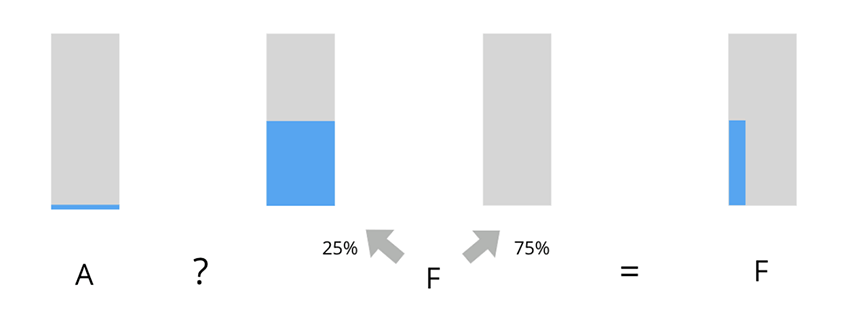

Now let us consider Case 3:

A: Certainly save one life.

F: Flip two fair coins; if it is double heads, you save 15 lives, anything else you save 0.

While F offers a higher expected value, you might not like the idea of a 75% chance of saving no one at all. But even if you don’t trust the guidance of expected value, we can argue that if you prefer C to A, and E to D, you should prefer F to A.

The probability of saving 15 lives with F can be represented as a single probability, 25%, or as two separate coin flips. We can break this up into two separate choices for illustration.

Suppose we are back in Case 1, and I give you the option to choose A or C. You choose C, and I flip the coin. It’s heads, and I give you a ticket to save 5 lives.

Now, I offer you a second bet, analogous to Case 2. Your ticket, while originally representing C, now represents D: saving 5 lives with certainty (since you’ve already received the ticket). I now offer you option E: let’s flip another coin, and if it is heads, you save 15 lives. If it is tails, you give me your ticket.

We’re already supposing that you prefer E over D. So you take the bet. By sequentially choosing C, then E, you have effectively chosen F over A.

Choosing F predictably loses, because we only get double heads 25% of the time. But framed as sequential choices, this becomes more palatable and intuitive. This is because choosing F is the same as choosing E-given-the-first-coin-is-heads. And you were already willing to bet on the first coin landing heads, in preferring C to A.

That is: you like C better than A (in virtue of C’s win condition), you like E better than D, and F just is a version of C with E as the “win condition” instead of D.

We can repeat this sequence of steps—next, I offer you the chance to save 30 lives if you get triple heads, an event that “hits” 12.5% of the time. I can keep raising the number of lives saved and lower the probability until we get our original example:

A: Certainly save one life.

B: Save all 1,000 lives with a 1% chance.

B can always be represented as a sequence of rational choices, given that you’re willing to take some modest bets like C over A. The move to sequential choices can help break down “but I’ll predictably lose”-type reactions into conditional strings of less risky gambles. But really, they’re just reminding you of the fact that you value one outcome a lot more than you value another. That is: if, in the face of a predictable loss, it’s hard to remember that you value saving a thousand lives a thousand times more than saving one, then you can remember, via coin flips, that you value saving two lives twice as much as saving one, value saving four lives twice as much as saving two, and so on.

Nothing special about getting saved by heads versus tails

Here’s another argument for why you should prefer B over A. Suppose Bob is on a deserted island, and will soon die of starvation. Then one day—salvation! A pirate ship is approaching the island and Bob senses his prospects for survival have greatly increased. The only catch: the pirate captain isn’t keen to toss overboard a barrel of rum in order to make room for Bob. He does, however, love to gamble.

Bob, in desperation, offers a bet: They will flip a coin, and if it is heads, Bob will be saved. If it is tails, then Bob will be left on the island.

The captain is willing to accept, but asks for a slight modification: Bob will only be saved on tails, and be left on the island on heads. It is a fair coin, and the probabilities for heads and tails are equivalent. Should Bob care? Surely not.

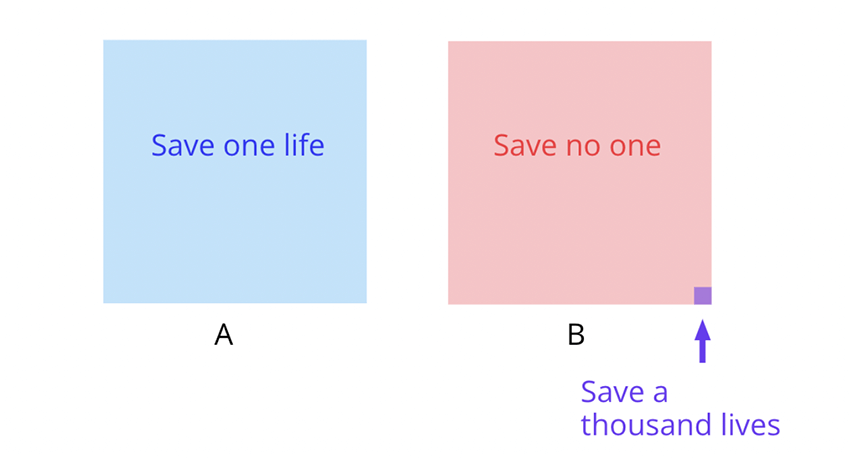

Now let’s generalize. Suppose there are 1000 people on the island and a thousand barrels of rum on the ship. The captain offers two choices. First, the captain offers to save one randomly selected person while leaving the other 999 shipwrecked people to die; let’s call this option A. Option A is saving one person with certainty.

The captain is still a gambling man, so he offers up option B as well. Rather than a coin flip, the captain offers to save all 1000 people and throw out his entire cargo if you pull a specific ball out of an urn with 100 balls, a 1% chance. The balls are all numbered “1” through “100.”

Suppose the pirate captain chooses ball 1 as the specific ball that, if chosen, saves all 1000 people. Bob is saved if ball 1 is picked because everyone is saved. Now suppose we instead save Bob if ball 2 is picked, and everyone else if ball 1 is picked, and no one if balls 3-100 are picked. Similar to the coin flip situation above, Bob shouldn’t care what ball saves him; he has a 1% chance of being saved in both cases because the odds of a particular ball being chosen is identical for all balls.

Similarly, we can move other people to different balls with the underlying odds and payoffs staying the same: Sally to ball 3, John to ball 4, and so on. We have 1000 people on the island and 100 balls, so we repeat this procedure until there are 10 people for each ball. Let’s call this option B’ (pronounced bee-prime).

We already know that B—a 1% chance to save all 1,000 lives—and B’ are equivalent scenarios from the perspective of Bob and the others whose lives are at stake. From each individual’s perspective, B and B’ offer the same chance of being rescued. B’ saves 10 people with certainty: whatever ball is chosen, 10 people are saved. Now, compare this with option A, which saves 1 person with certainty. It is clear we should choose B’—and thus, B—over A.

In skyscraper terms, what we’re doing here is taking floors off of the top of B’s skyscraper, and moving them down to the ground. Eventually, we get a cityscape that is perfectly flat and everywhere taller than A.

What would everyone prefer?

Here’s a final argument for B over A, analogous to the “veil of ignorance”. Suppose that 1,000 people are drowning. Option A saves one random person with certainty, and option B saves everyone with a 1% chance.

Under A, each person has a 0.1% chance of surviving, whereas under B, each individual has a 1% chance of being saved. So everyone drowning wants you to choose B: it maximizes their individual chances of survival.

In this scenario, choosing option B is surely the correct choice. Choosing A—saving a random person’s life at the cost of making everyone 10 times less likely to survive—no longer sounds so heroic.

This argument doesn’t apply if it is fixed in advance which of the 1,000 people option A would save. That person would then be straightforwardly better off under A. But there are reasons to think that version of the case is distorting. After all, it shouldn’t really matter who is saved. Giving everyone an equal 1/1,000 chance of being the one saved cannot be morally worse than giving all of the chances to one arbitrary person—to think otherwise would violate the equal consideration of interests. And we’ve seen that a 1% chance of saving all 1,000 lives is better than giving a 1/1,000 chance to each. So we should judge that B is also better than saving an identified individual.

Taking Responsibility

We’ve seen three arguments for choosing B over A, even if it means you will predictably lose. Our examples have been highly simplistic: thinking of coins, urns, and lives. Each of these things can be easily and discretely broken up into objective probabilities and utilities, and it seems uncontroversial to treat all lives as bearing equal value.

In the real world, we often don’t have such luxuries. Suppose that you play the cello and live in an apartment building, and must decide whether to practice at moderately-late times before rehearsals. If you don’t practice, you will play poorly in your rehearsal, but you might anger your neighbors if you practice late.

How much is practicing worth to you? What is the likelihood your neighbors will get angry if you play? What, exactly, are the cityscapes here?

EUM won’t tell you these things. You need to decide for yourself. More specifically, you need to decide the utilities or values of the possible outcomes and their probabilities. Some things matter to you more than others, and some events are more plausible than others.4 And sometimes, a given action affects what matters to you differently, depending on the state of the world. Somehow, you have to weigh this all up and make a decision.

EUM just says to respond to this predicament in a way that satisfies certain constraints. These constraints impose useful discipline, especially when coupled with certain sorts of intuition pumps. To estimate the likelihood of a neighbor being upset, I might ask myself, “Suppose I had no stake in my neighbor’s feelings. Would I rather earn 1 million dollars if my neighbor complains, or if a ball is picked from an urn with p% chance?” To think about the value of practicing, I could ask myself, “how high a risk of angering my neighbors would it take to outweigh doing well in rehearsal?”

Still, most of the work—including generating these sorts of intuitions—is on you. If your answers are inconsistent, EUM tells you to revise them, but it doesn’t tell you how. There may not even be any objectively correct answers (or if there are, no one can tell you for sure what they are). You have to decide.

It can be illuminating to understand your choices as always “taking a stance,” such that having values and beliefs is not some sort of optional thing you just sometimes do, when the world makes it convenient, but rather a thing that you are always doing, with every movement of your mind and body.5

We often don’t like to think about it because thinking of trade-offs brings to mind the sacrifice in our choices. This is especially poignant when we think of the value we get from our personal resources and money compared to what someone in dire poverty might gain from the same resources.

Expected Utility Maximization is about achieving consistency and harmony in your decisions and dispositions. You could coherently value any number of different things. But once you’ve determined that you’d rather take a 50% shot at Y than a certainty of X, you’ve already decided that you value Y at least twice as much as X. And if you’d rather have a 50% shot at Z than a certainty of Y, you value Z at least twice as much as Y. At this point, your values no longer make sense if you suddenly prefer the certainty of X over a 25% shot at Z.

If you simply value everyone’s well-being equally, as utilitarianism does, then maximizing expected well-being is one plausible approach to acting in the face of uncertainty (though it comes with a variety of theoretical difficulties that haven’t been discussed here).6 But even if your values differ from those of utilitarians, you may still find that you seek to maximize the expectation of some or other (possibly quite rich and complicated) set of values, or else you fail to have coherent values at all.7

About the Authors

Joe Carlsmith has a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Oxford. He works as a senior research analyst at Open Philanthropy, where he focuses on existential risk from advanced artificial intelligence. He also writes independently about various topics in philosophy and futurism.

Vikram Balasubramanian studies Philosophy at Trinity College Dublin as a U.S.-Ireland Alliance Mitchell Scholar. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, with degrees in Philosophy in the School of Arts and Sciences, and Statistics at the Wharton School. Vikram is interested in combining philosophy with statistics to research social dynamics.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Compare how statisticians calculate the expectation of a random variable: Take an event, and multiply it by the likelihood of it happening. ↩︎

Slovic, P. (2007). “If I look at the mass I will never act”: Psychic numbing and genocide. Judgment and Decision Making, 2(2), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500000061 ↩︎

Though note that these substantive aggregationist value claims go beyond the formal structure of EUM as a (value-neutral) decision theory. ↩︎

You might even wish to consider the likelihood that your theory of chance that you used to determine probabilities is correct, as some philosophers have suggested. ↩︎

See, for example, the problems that infinities pose for utilitarian ethics. ↩︎

A note on authorship: this essay was adapted (with permission) from Joe Carlsmith’s essay series on Expected Utility Maximization, with editing by Vikram Balasubramanian and the editors of utilitarianism.net. ↩︎