Abstract

Important parts of economics (including parts of welfare economics) do not rely on interpersonal comparisons of cardinal utility, such as ‘positively’ deriving demand curves from indifference maps and analysing conditions for Pareto optimality. However, some parts of welfare economics—those related to equality and distributional issues—do need interpersonal comparisons of cardinal utility. While many modern economists reject these interpersonal comparisons, this essay argues in their favour from commonsense, conceptual, and practical perspectives. In particular, Edgeworth’s concept of a just perceivable increment of happiness is used to assist interpersonal comparison. With an additional axiom of Weak Majority Preference Criterion (WMP), the utilitarian result that social welfare is an unweighted sum of individual utilities is also derived. WMP is compelling as it just requires that the perceivable preference of at least half of all individuals should dominate the non-perceivable dis-preference of the other half.

Many students of economics and philosophy have been puzzled by whether utility is cardinally or only ordinally measurable, and whether interpersonal comparisons of utility are possible in principle and in practice. This essay attempts to answer these questions, using simple arguments understandable by most students in economics and philosophy.

Is Utility Ordinal or Cardinal?

After the ordinalist revolution in economics around the 1930s associated with the use of indifference curve analysis (instead of marginal utility), most economists accept the position of Robbins (1932, 1938) in believing that every mind is totally inscrutable to others, making interpersonal utility comparisons impossible (or at least unscientific), even just in principle.1

Apart from the issue of interpersonal comparability, there is also the associated issue of whether utility is cardinally measurable or only ordinally measurable. Ordinal measurability involves only ranking preferences (i.e. higher, lower, or the same; or: prefer, disprefer, indifference); cardinal measurability involves also the intensities of preference. Consider three alternatives x, y, and z. With only ordinal measurability, you may prefer x to y, and prefer y to z. However, you cannot say whether your preference of x over y is more intense than that of y over z, or vice versa. Such comparisons involve cardinal utility.

The controversies in measuring and comparing utility are partly due to different notions of ‘utility’. The initial usage of this word probably meant the usefulness of something (a commodity, a policy, a measure, etc.) to some person(s). In this sense, utility is obviously cardinal, as something can be more or less useful. This initial concept of utility probably developed into the concept of utility as satisfaction in classical economics (in and around the 19th century) and the early stage of neoclassical economics (over 1900 to 1930s). This concept of utility is also clearly cardinal since people can be more or less satisfied. However, after the popularization of indifference map analysis in the 1930s, utility has been used in modern economics mostly in its ordinal sense; this is the ‘ordinalist revolution’.2

The ordinalist concept of utility simply represents an ordering of preferences. Utility of x being higher than that of y only means that the decision maker prefers x to y.3 In this sense of the pure representation of ordinal preference, then of course utility is only ordinally (but not cardinally) measurable. This ordinalist concept of utility also makes interpersonal comparisons of utility difficult, if not impossible.

The confinement to ordinal utility aims to make economic analysis more objective or scientific. This is similar to the behaviorist revolution in psychology associated with Watson (1913) and Skinner (1957). Classical psychologists spoke of concepts like mind and consciousness, and they used introspection in their analysis. Watson-Skinner behaviourism prohibits analysing anything subjective (including thoughts and feelings); it holds that only actual behaviours are the proper subject matter of psychology. This allowed psychology to make huge advances in becoming more objective, but also caused some to feel that it had “gone out of its mind … and lost all consciousness” (Chomsky, 1959, p.29). The reaction against the excesses of behaviourism resulted in the cognitive revolution that began in the 1950s.

Similarly, the excess in the ordinalist revolution in economics has been partly reversed by the increasing attention to the analysis of happiness. Since the first publication on happiness issues by an economist (Easterlin 1974), contributions from economists have mushroomed over the last two to three decades.4 In contrast to utility, happiness is a much more subjective and cardinal concept. Economists are more accepting of cardinal measurement and interpersonal comparison when discussing happiness rather than utility.

In an important sense, feelings in general and happiness in particular are more basic and important than behaviours and actions (including economic actions like consumption and production), which are more derivative, at least for conscious actors like humans or other animals (rather than non-conscious economic entities like firms). In fact, I regard happiness as ultimately the only thing of intrinsic value (Ng 2022, Ch.5); all other things can only be of instrumental value in promoting happiness, including in others and in the future. In this sense, happiness is more basic, ultimate, and intrinsic than behaviours, actions and revealed preferences. The basicness of happiness does not mean that the analyses of these other things are not useful. However, we should not exclusively focus on those other things, as happened in psychology under behaviourism and in economics under ordinalism.

Does Welfare Economics Need Interpersonal Utility Comparison?

An important reason that many modern economists regard interpersonal utility comparisons as unnecessary in economics (including welfare economics) is due to their focus on the concept and analysis of Pareto optimality. As such, they focus mainly on efficiency, largely ignoring issues of equality and distribution.

The Pareto Principle is the compelling idea that, if someone is made better off, without anyone else being made worse off, this is a social improvement—that is, social welfare has increased. Correspondingly, Pareto optimality is a situation where no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Focussing on the conditions for Pareto optimality as such, no interpersonal comparisons of utility are needed. However, if we have to compare the value of two alternative outcomes (whether Pareto-optimal or non-optimal), we typically have to make interpersonal comparisons of utility since typically someone is better off or worse off in one outcome than another, and someone else is in the opposite situation. For example, in comparing outcome x to outcome y, Xander may be better off in x than in y, while Yasmin is better off in y than in x. We thus need interpersonal comparisons of utility to determine which outcome is overall better.

Still, dispensing with cardinal utility and interpersonal utility comparison can be adequate for some economic problems. For example, we may derive the demand curve for a certain commodity by an individual from her indifference map, by varying the price of this commodity, while holding other things (including her income level and her preferences) unchanged, as is often done in entry-level economics classes. We can do this for all consumers in the relevant market. We may then sum these individual demand curves for the same commodity horizontally to derive the market demand curve. We may then use this market demand curve with the supply curve to analyse the equilibrium price, and shift either curve to do comparative static analysis. For such ‘positive’ analysis, we do not need either cardinal utility or interpersonal utility comparisons.

While such a ‘positive’ economic analysis is useful, it does not exhaust all economic issues. Economists, and welfare economists in particular, are also interested in what happens to the level of social welfare. Social welfare depends not only on Pareto efficiency, but also on the distribution of income/consumption/wealth. (In the usual a-temporal framework of simple welfare economic analysis, these three are equivalent.) A more complete welfare economics should tackle both efficiency and distributional issues, thus requiring interpersonal comparisons of utility.

The Commonsense Case for Cardinal Utility and Interpersonal Utility Comparisons

Consider the following three alternatives

x = Your current situation;

y = Your current situation plus being bitten by a non-poisonous ant;

z = You are thrown into a pool of boiling water.

Then, other things being equal, obviously you prefer x to y and also prefer y to z. So, ordinal preference makes sense. However, this is not all. Your preference for y over z is obviously very much higher or more intense than your preference for x over y. The intensity is probably many thousand times higher. This makes cardinal utility sensible.

In fact, most people will also agree that your preference for y over z is at least a hundred times higher than _my _preference of x over y. This is an interpersonal comparison of cardinal utilities. True, for cases without such huge value differences, making precise cardinal measurement and interpersonal comparisons of utilities may be difficult. But mere practical difficulty is very different from being impossible even in principle. Denying these principles is not going to help improve the precision and reliability of cardinal measurement and interpersonal comparisons of utilities. (For further discussion of the measurement and interpersonal comparison of utility/happiness, see my open-access book Happiness—Concept, Measurement, and Promotion, especially Ch.6.)

The Practical Measurement and Interpersonal Comparison of Utilities

Common sense and psychological studies show that human beings are not infinitely sensitive or discriminative. Suppose that you find it best to add two spoons (of a given size) of sugar to a cup of coffee of given amount and intensity. Thus, you prefer 2 to 1.5 (spoons of sugar). However, obviously you cannot taste a difference between 2 and 1.9999. Thus, in the presence of finite sensibility, our explicit preferences (including indifferences) may not be transitive. One may be indifferent between 2 and 1.95, and also indifferent between 1.95 to 1.9. Yet, one may prefer 2 to 1.9. This concept was discussed as early as 1881 by Francis Edgeworth (1845-1926), and touched on even earlier by Jeremy Bentham (1749-1832); see Tännsjö (1998). Edgeworth took it as axiomatic, or, in his words “a first principle incapable of proof”, that the “minimum sensible” or the just perceivable increments of pleasures for all persons, are equal (Edgeworth, 1881, pp. 7ff., pp. 60 ff.). I derived this result and utilitarianism (that social welfare is just an unweighted or equally weighted sum of individual utilities) from more basic axioms (Ng 1975). The crucial axiom is the

Weak Majority Preference Criterion (WMP): For any two alternatives x and y, if no individual prefers y to x, and (1) if s, the number of individuals, is even, at least s/2 individuals prefer x to y; (2) if s is odd, at least (s - 1)/2 individuals prefer x to y and at least another individual’s utility level is not lower in x than in y, then social welfare is higher in x than in y.

Though WMP is weaker than the strong Pareto principle, it is sufficient for our purpose.5 The reason why WMP leads us to interpersonal utility comparison and the utilitarian social welfare function is not difficult to see. WMP requires that utility differences sufficient to give rise to preferences of half of the population must be regarded as socially more significant than utility differences not sufficient to give rise to preferences (or dispreferences) of another half. Since any group of individuals comprising 50 per cent of the population is an acceptable half, this effectively makes a just perceivable increment of utility of any individual an interpersonally comparable unit that has to be treated the same in determining the social welfare. This effectively also makes the social welfare function utilitarian, i.e., social welfare is just the unweighted sum of individual utilities. This is shown further below.

Considering only cases where the number of individuals is even, as long as 50% of the population are made perceivably better off and the other 50% not perceivably worse off, social welfare increases according to WMP. Conversely, as long as 50% are made perceivably worse off and the other 50% not perceivably better off, social welfare decreases. Thus, taking the limit, social welfare stays unchanged as 50% of the population are made just unnoticeably better off and the other 50% just unnoticeably worse off (reasonably assuming that social welfare is a continuous function of individual utilities).

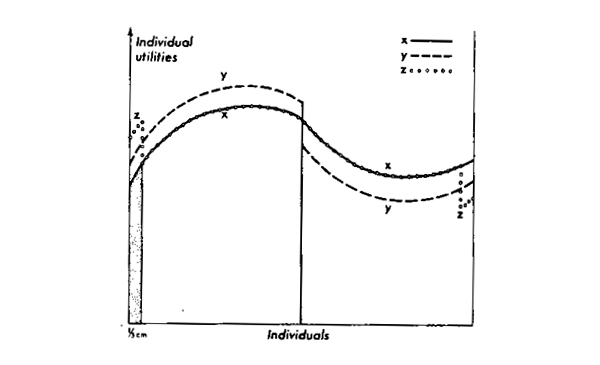

In Figure 1 (Ng & Singer, 1981) all the s individuals are arranged along the horizontal axis and individual utilities are represented by the vertical axis. Starting from an initial situation x, let the curve x represent the utilities of the various individuals. For example, if each individual occupies a distance of one-third of a centimeter (along the horizontal axis), the utility of the first individual in situation x is the shaded area. The curve x need not be continuous. This does not affect our argument. Consider another situation y which, in comparison to x, involves making the first s/2 individuals just un-perceivably better off and the rest just un-perceivably worse off. From WMP and the preceding argument, social welfare remains unchanged. Now, starting from situation y_ _(see the curve y), consider another situation z. In comparison to y, z involves making another 50 per cent (the first individual, and the second half of all individuals except the last one) just un-perceivably better off and the other 50 per cent (the last individual and the first half of all individuals except the first) just un-perceivably worse off. Hence, social welfare again remains unchanged. Since there is no change between x and y, or between y and z, social welfare must be same at x as at z. Comparing x and z, we see that all have exactly the same levels of utilities except the first and the last individuals. The first individual’s utility has increased by two units and the last decreased by two units. This demonstration does not depend on the choice of these two particular individuals, since WMP applies to any 50 per cent of individuals. Thus we may conclude that, irrespective of the initial situation, if we increase the utility of any one individual by two units and decrease that of any other by two units, holding those of all others unchanged, social welfare must remain unchanged. Effectively, this leads us to the utilitarian social welfare function of the unweighted sum of individual utilities. (See Ng, 1975, for a formal and rigorous proof.) For further discussion of the issues of practical comparison, see Argenziano & Gilboa (2019) and Ng (2024).

Concluding Remarks

Even short of accepting the compelling utilitarian result shown in the previous section, just accepting the (strong) Pareto principle alone implies that social welfare is an increasing function of individual utilities. With all other individual utilities held unchanged, an increase in the utility of any individual must lead to an increase in social welfare.6 But, obviously, for changes that make some individual(s) better off and some worse off—as is typical of most social changes—we need interpersonal comparisons of utility to evaluate the effects of such changes on social welfare. Even in the obvious case where only a few very rich and self-centred persons were made slightly richer, and most others were made much poorer, other things being equal, we still would not be able to say anything about social welfare without interpersonal utility comparisons. Thus, dispensing with interpersonal utility comparison would make welfare economics lame and paralyse most public decisions and their evaluations.

About the Author

Yew-Kwang Ng is an emeritus professor in the Department of Economics at Monash University, Australia. He is a Jubilee Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, and in 2007, received the highest award (Distinguished Fellow) of the Economic Society of Australia.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

References

- Argenziano, Rossella & Itzhak Gilboa (2019). Perception-theoretic foundations of weighted Utilitarianism. The Economic Journal, 129 (May), 1511–1528 DOI: 10.1111/ecoj.12622

- Chomsky, N. (1959). A review of BF Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language, 35(1): 26-58.

- Dominko, M. & Verbič, M. (2019). The economics of subjective well-being: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(6): 1973–1994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0022-z

- Easterlin, Richard A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89-125). Academic press.

- Edgeworth, Francis Y. (1881). Mathematical Psychics: An Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Moral Sciences. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (1975). Bentham or Bergson? Finite sensibility, utility functions, and social welfare functions. Review of Economic Studies, 42:545-70.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (1999). Utility, informed preference, or happiness? Following Harsanyi’s argument to its logical conclusion. Social Choice and Welfare, 16(2): 197-216.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (2022). Happiness: Concept, Measurement, and Promotion, Springer, open access at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-33-4972-8

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (2024). Utilitarianism: Overcoming the difficulty of interpersonal comparison, Singapore Economic Review, online published only so far.

- https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590824450012

- Ng, Yew-Kwang & Singer, Peter (1981). An argument for utilitarianism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 11: 229-239.

- Pareto, Vilfredo (1906/1971). Manual of Political Economy (trans A.S. Schwier, 1971).

- Robbins, Lionel (1932). An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. Macmillan, London.

- Robbins, Lionel (1938). Interpersonal comparison of utility: a comment, Economic Journal, 48: 635-641.

- Skinner, Burrhus Frederick (1957).Verbal Behavior. Acton, Massachusetts: Copley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58390-021-5.

- Tännsjö, Torbjörn (1998). Hedonistic Utilitarianism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press/Columbia University Press.

- Watson, John B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20.2: 158-177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074428

For simplicity, I ignore in this paper the possible divergences between utility/preference and happiness/welfare, as may be due to: ignorance or imperfect foresight, a concern for others, irrationality; see Ng (1999) for details. ↩︎

The concept of indifference curves was touched on by Edgeworth in his 1881 book, and the curves actually drawn by Pareto in his 1906 book. ↩︎

Note from the Editors: this is very different from the philosophical use of ‘utility’ to refer to impartial welfare value. Economists’ “utility functions” can reflect all sorts of non-utilitarian values, including partial and non-welfarist ones. ↩︎

For a bibliometric analysis of the economics of happiness, see Dominko & Verbič (2019), which shows, among others, a big surge after the global financial crisis in 2008. ↩︎

For an axiom/condition, the weaker the better, given the same results derived. The weak Pareto principle requires all individuals to prefer x over y to ensure social preference or higher social welfare; the strong Pareto principle requires only that some individual/s prefers/prefer x to y with no individual prefers y to x. ↩︎

Social preference and higher social welfare are taken as equivalent. ↩︎