The Mere Means Objection

Critics often allege that utilitarianism objectionably instrumentalizes people—treating us as “mere means” to the greater good, rather than properly valuing individuals as “ends in themselves”.1 In this article, we assess whether this is a fair objection.

There is something very appealing about the Kantian Formula of Humanity, that one should “act in such a way as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of anyone else, always as an end and never merely as a means.”2 If utilitarianism were truly incompatible with the plain meaning of this formula, then that would constitute a serious objection to the theory. For it would then be shown to be incompatible with the basic point that people have intrinsic value as ends in themselves.

Why think that utilitarianism treats anyone merely as a means? Three possibilities seem worth exploring. The first involves mistakenly leaving out the crucial word “merely”, though this radically changes the meaning of the Formula of Humanity in a way that undermines its plausibility. The second hinges on the utilitarian preference for saving lives that are themselves more instrumentally useful for indirectly helping others. And the third involves a distinctly Kantian interpretation of what is essential to treating someone as an end in themselves. But as we will see, none of these three moves validates the conclusion that utilitarianism violates the plain meaning of the Formula of Humanity, or literally treats anyone as a “mere means”.

Using as a Means

Utilitarianism allows people to be used as a means to bring about better outcomes. For example, in stylized thought experiments, it implies that one person should be killed to save five. More generally, it allows harm to be imposed on some in order to secure greater overall benefits for others. But many ways of using others are morally innocuous. As Kantians will agree: If you ask a stranger for directions, you are using them as a means, but not objectionably. Asking someone for directions is compatible with still regarding them as intrinsically valuable, or an end in themselves. Is utilitarian sacrifice different in a way that makes it incompatible with such moral regard?

There are important differences between the two cases. Most obviously, utilitarian sacrifice involves harming (sometimes even killing) the targeted individual. So it’s not as innocuous as asking for directions: there is a significant moral cost here, which could only be justified by sufficiently great compensating moral gains. Even so, on the crucial question of whether utilitarians still regard the sacrificed individual as an intrinsically valuable end in themselves, the answer is a clear YES. After all, the utilitarian agent would be willing to sacrifice other goods of significant value3—including their own interests—to spare the sacrificed individual of their burden. But one obviously would not be willing to sacrifice in such a way for any entity that one regarded as a mere means, entirely lacking in moral importance.4 So we see that the utilitarian regards the sacrificed individual as morally important (emphatically not a mere means), albeit not as important as five other people combined.

Utilitarianism counts the well-being of everyone fully and equally, neglecting none. So, while it (like other theories) permits some forms of using people as a means, it never loses sight of the fact that all individuals have intrinsic value. That is precisely why the theory directs us to do whatever will best help all those individuals. This may lead to outcomes where some particular individuals are disadvantaged. But it’s important not to conflate ending up worse-off with counting for less in the process of determining what would be best overall (counting everyone’s interests equally).

For example, suppose a group of friends draw lots to determine who should perform some unpleasant chore. The person who draws the short straw is not thereby mistreated in any way: the bad (for him) outcome is the result of a fair process that treats him the same as everyone else in the group. In a similar way, utilitarianism counts everyone’s interests equally, even when it yields results that are better for some than for others. Since everyone is counted fully as ends in themselves, it’s not accurate to claim that utilitarianism treats anyone as a “mere means”.

By contrast, utilitarianism does treat non-sentient things, like the environment, as having merely instrumental value. Environmental protection is immensely important, not for its own sake, but for the sake of people and other sentient beings. There is a big difference between how utilitarianism values the environment and how it values people, which is another way to see that the theory does not value people merely instrumentally.

Instrumental Favoritism

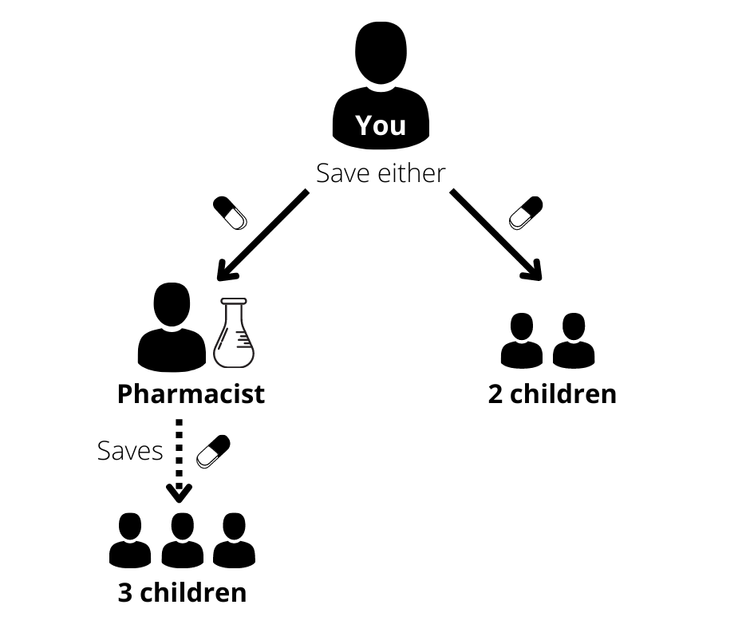

Suppose that you are faced with a medical emergency, but only have enough medicine to save either one adult or two children. Two children and an adult pharmacist are on the brink of death, and three other children are severely ill, and would die before anyone else is able to come to their assistance. If you save the pharmacist, she will be able to manufacture more medicine in time to save the remaining three severely ill children (though not in time to save the two that are already on the brink). If you save the two children, all the others will die. What should you do?

By utilitarian lights, the answer is straightforward: you should save the pharmacist, and thereby save four individuals (including three children), rather than only saving two children. It does not matter whether you save an individual directly (by giving them medicine yourself) or indirectly (by enabling the pharmacist to give them medicine); all that matters is that they are saved.

But some critics object to this. Frances Kamm, for example, claims:

To favor the person who can produce [extra utility] is to treat people “merely as means” since it decides against the person who cannot produce the extra utility on the grounds that he is not a means. It does not give people equal status as “ends in themselves” and, therefore, treats them unfairly.5

In our example, the two children on the brink miss out on the medicine because—unlike the pharmacist—they are unable to save additional lives. While the two children together have greater intrinsic value than the pharmacist alone, the pharmacist has vastly greater instrumental value in this context, as only by saving her are we thereby able to (indirectly) save the three other children. And when the intrinsic values of saving these four lives are combined, it outweighs the intrinsic value of saving just two children.

Kamm charges that, in deciding against the two children on these grounds, we would fail to give them “equal status as ends in themselves”. But why think this? As the above reasoning makes clear, the utilitarian does not ascribe any extra intrinsic value to the pharmacist. The pharmacist is thus not regarded as any more important as an end in herself. Intrinsically, or in herself, she may be regarded equally to any other individual.6 We prioritize saving her over the two children simply because we can thereby save the three other children in addition. The utilitarian’s disagreement with Kamm stems not from the utilitarian unfairly giving extra weight to the pharmacist, but from Kamm’s failure to give equal weight to the three children we could save by means of saving the pharmacist.

To emphasize this point, consider a variation of the case in which the pharmacist is replaced with a duplicator machine.7 Suppose you could either save the two children on the brink of death immediately, or place the medicine in a duplicator that will (after some time) produce enough medicine to save the other three severely ill children. In simply opting to save the larger number, the utilitarian is clearly not treating anyone as a “mere means”. But how could it possibly be morally worse to save the pharmacist in addition to those three children?

That said, there are many cases in which instrumental favoritism would seem less appropriate. We do not want emergency room doctors to pass judgment on the social value of their patients before deciding who to save, for example. And there are good utilitarian reasons for this: such judgments are apt to be unreliable, distorted by all sorts of biases regarding privilege and social status, and institutionalizing them could send a harmful stigmatizing message that undermines social solidarity. Realistically, it seems unlikely that the minor instrumental benefits to be gained from such a policy would outweigh these significant harms. So utilitarians may endorse standard rules of medical ethics that disallow medical providers from considering social value in triage or when making medical allocation decisions. But this practical point is very different from claiming that, as a matter of principle, utilitarianism’s instrumental favoritism treats others as mere means. There seems to be no good basis for that stronger claim.

Kantian Interpretations

Kantians and utilitarians disagree about how to respond to the intrinsic value of each person. Utilitarians believe that the correct way to appreciate the intrinsic value of all individuals is to count their interests equally in the utilitarian calculus. Kantians offer a different account, typically appealing to considerations of possible or actual consent.8 Advocates of the “mere means” objection may further claim that, in failing to follow the Kantian standard for how to appreciate the intrinsic value of persons, utilitarians fail to regard people as intrinsically valuable at all. But that is uncharitable. Everyone agrees that people are ends in themselves; the disagreement is just about what follows from that morally.

Different moral theories, such as utilitarianism and Kantianism, offer different accounts of the morally correct way to respond to the intrinsic value of persons. We make no attempt to adjudicate that dispute here. Someone who is convinced by the arguments for Kantianism may certainly be expected to reject utilitarianism on that basis. But there is no independent basis for rejecting utilitarianism merely on the grounds that it violates Kantian standards for treating people as ends in themselves. We might just as well turn the objection around and charge Kantians with violating utilitarian standards for how to value people equally as ends in themselves. Either charge would seem equally question-begging, and provides the target with no independent grounds for doubting their view.

Conclusion

We’ve seen that it’s inaccurate to claim that utilitarians treat people as “mere means”. All plausible moral theories sometimes allow people to be treated as a means (while also respecting them as ends in themselves). When utilitarianism allows such treatment, even in the most extreme cases of “utilitarian sacrifice”, it does not thereby treat the affected individuals as mere means. Even those who end up worse off are not subject to procedural unfairness or disregard: their interests are counted fully and equally to anyone else’s, as befits their intrinsic value. And while Kantians disagree with utilitarians about the right way to respond to the intrinsic value of persons, everyone agrees that individual persons are intrinsically valuable, and not mere means to some other goal.

But there may be other, closely related, objections that people sometimes have in mind when they accuse utilitarianism of treating people as mere means. Some may have in mind the “separateness of persons” objection—criticizing utilitarianism for treating tradeoffs between lives the same way as tradeoffs within a life—which we address separately. Others may be concerned about how utilitarianism (in theory) permits instrumental harm when the benefits outweigh the costs. Our discussion of the rights objection addresses this concern in more detail. Note that in practice, utilitarians tend to be strongly supportive of respecting rights, as societies that respect individual rights tend to do a better job of promoting overall well-being.

How to Cite This Page

Resources and Further Reading

- Samuel Kerstein (2019). Treating Persons as Means, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Derek Parfit (2011). On What Matters: Vol 1. Oxford University Press. Chapter 9: Merely as a Means.

Strictly speaking, this objection applies to all (aggregative) consequentialist theories. The responses we offer on behalf of utilitarianism in this article would equally apply in defense of other consequentialist theories. ↩︎

Kant, Immanuel (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, translated by Jonathan Bennett. ↩︎

Specifically, they would be willing to sacrifice goods that added up to an equal or lesser loss of well-being value, in order to relieve this burden. ↩︎

Cf. Parfit, D. (2011). On What Matters: Vol 1. Oxford University Press. Chapter 9: Merely as a Means. ↩︎

Kamm, F. (1998). Are There Irrelevant Utilities? in Morality, Mortality Volume I: Death and Whom to Save From It. Oxford University Press, p. 147. ↩︎

Strictly speaking: her interests are given equal weight, but if she has lower remaining life expectancy than the children (and hence correspondingly less future well-being at stake), then the intrinsic value of her future life may be lower than that of those with longer yet to live. ↩︎

Thanks to Toby Ord for suggesting this variant. ↩︎

For example, they may claim that you should not treat people in ways that they either do not consent to, or could not reasonably consent to. ↩︎