“To what shall the character of utility be ascribed, if not to that which is a source of pleasure?”

Introduction

A core element of utilitarianism is welfarism—the view that only the welfare (also called well-being) of individuals determines how good a particular state of the world is. While consequentialists claim that what is right is to promote the amount of good in the world, welfarists specifically equate the good to be promoted with well-being.

Philosophers use the term “well-being” to refer to what’s good for a person, as opposed to what’s good per se, or “from the point of view of the Universe” to use Sidgwick’s poetic phrase. Utilitarianism holds that well-being is always good from the point of view of the universe, and not just good for the individual. But other views may coherently deny this. For example, one might think that the punishment of an evil person is good, and moreover it’s good precisely because that punishment is bad for him.

In this chapter, we explore different accounts of the intrinsic or basic welfare goods—as opposed to things that are only instrumentally good for you. For example, happiness is (plausibly) intrinsically good for you; it directly increases your well-being. In contrast, money can buy many useful things and is thus instrumentally good for you, but does not in itself constitute well-being. (We can similarly speak of things that are intrinsically bad for you, like misery, as “welfare bads”.)

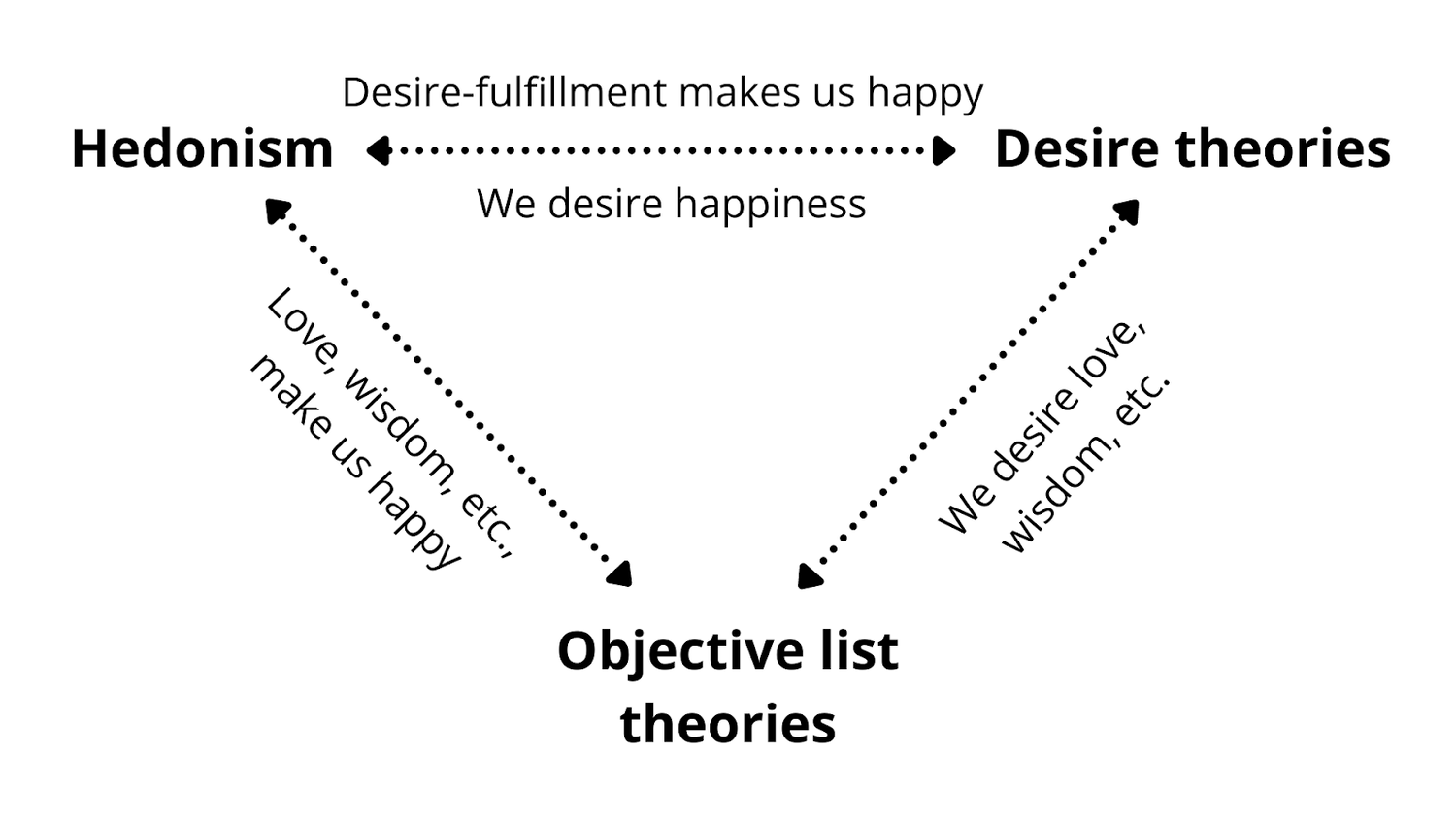

However, there is widespread disagreement about what constitutes well-being.2 What things are in themselves good for a person? The diverging answers to this question give rise to a variety of theories of well-being, each of which regards different things as the components of well-being. The three main theories of well-being are hedonism, desire theories, and objective list theories.3 The differences between these theories are—in today’s world, at least—of primarily theoretical interest; they overlap sufficiently in practice that the immediate practical implications of utilitarianism are unlikely to depend upon which of these, if any, turns out to be the correct view. But as we’ll see, future technology could severely disrupt this practical overlap. It may then matter greatly which account of well-being we accept.

Hedonism

The theory of well-being that is built into classical utilitarianism is hedonism.4

Hedonism is the view that well-being consists in, and only in, the balance of positive minus negative conscious experiences.5

On this view, the only basic welfare goods are pleasant experiences such as enjoyment and contentment. Conversely, the only basic welfare bads are unpleasant experiences such as pain and misery. For the sake of readability, we refer to pleasant experiences as happiness and to unpleasant experiences as suffering.

The hedonistic conception of happiness is broad: It covers not only paradigmatic instances of sensory pleasure—such as the experiences of eating delicious food or having sex—but also other positively valenced experiences, such as the experiences of solving a problem, reading a novel, or helping a friend. Hedonists claim that all of these enjoyable experiences are intrinsically valuable. Other goods, such as wealth, health, justice, fairness, and equality, are also valued by hedonists, but they are valued instrumentally. That is, they are only valued to the extent that they increase happiness and reduce suffering.

When hedonism is combined with impartiality, as in classical utilitarianism, hedonism’s scope becomes universal. This means that happiness and suffering are treated as equally important regardless of when, where, or by whom they are experienced. From this follows sentiocentrism, the view that we should extend our moral concern to all sentient beings, including humans and most non-human animals, since only they can experience happiness or suffering. Alternatively, non-utilitarian views may accept hedonism but reject impartiality, thus restricting hedonism’s scope to claim that only the happiness of a specified group—or even a single individual6—should “count” morally.

The notion at the heart of hedonism, that happiness is good and suffering is bad, is widely accepted. The simple act of investigating our own conscious experiences through introspection appears to support this view: The goodness of happiness and the badness of suffering are self-evident to those who experience them.7 Importantly, happiness seems good (and suffering bad) not simply because they help (or hinder) us in our pursuit of other goods, but because experiencing them is good (or bad) in itself.

However, what makes hedonism controversial is that it implies that:

- All happiness is intrinsically good for you, and all suffering intrinsically bad.

- Happiness is the only basic welfare good, and suffering the only basic welfare bad.

Critics of hedonism dispute the first claim by pointing to instances of putative evil pleasures, which they claim are not good for you. And they often reject the second claim by invoking Robert Nozick’s “experience machine” thought experiment to argue that there must be basic welfare goods other than happiness. We explain each objection, and how hedonists can respond, in turn.

The “Evil Pleasures” Objection

Critics often reject the hedonist claim that all happiness is good and all suffering bad. Consider a sadist who takes pleasure in harming others without their consent. Hedonists can allow that nonconsensual sadism is typically overall harmful, as the sadist’s pleasure is unlikely to outweigh the suffering of their victim. This clearly justifies disapproving of nonconsensual sadism in practice, especially with a multi-level utilitarian view. Under that view, we might assume that finding the rare exceptions to this rule would have little practical value. However, the risk of mistakenly permitting harmful actions means that we would be better off establishing a general prohibition on harming others without their consent.

Still, on a purely theoretical level, we may ask: What if there were many sadists, collectively rejoicing in the suffering of a single tortured soul? If their aggregate pleasure outweighs the suffering of the one, then hedonistic utilitarianism implies that this is a good outcome, and the sadists act rightly in torturing their victim. But that seems wrong.

At this point, it’s worth distinguishing a couple of subtly different claims that one might object to: (i) the sadists benefit from their sadistic pleasure, and (ii) the benefits to the sadists count as moral goods, or something that we should want to promote (all else equal).

To reject (i) means rejecting hedonism about well-being. But if sadistic pleasure does not benefit the sadist, then this implies that someone who wants to make the sadist worse off (for whatever reason) could not achieve that by means of blocking their sadistic pleasure. And that seems mistaken.

Alternatively, one might retain hedonism about well-being while respecting our intuitive opposition to “evil pleasures” by instead rejecting (ii), and denying that benefiting sadists at the expense of their victims is reasonable or good. This would involve rejecting utilitarianism, strictly speaking, though a closely related consequentialist view that merely gives equal weight to all innocent interests (while discounting illicit interests) remains available, and overlaps with utilitarianism in the vast majority of cases.

Hedonistic utilitarians might seek to preserve both (i) and (ii) by offering an alternative explanation of our intuitions. For example, we may judge the sadists’ characters to be bad insofar as they enjoy hurting others, and so they seem likely to act wrongly in many other circumstances.8

When “evil” pleasures are detached from their usual consequences, it becomes much less clear that they are still bad. Imagine a universe containing only a single sadist, whose sole enjoyment in life comes from their false belief that there are other people undergoing significant torment. Would it really improve things if the sadist’s one source of delight was taken away from them? If not, then it seems like sadistic pleasure is not intrinsically bad after all. (Though we can, of course, still disapprove of its instrumental badness in real-life circumstances.) Even so, if we think it would inherently improve things to replace the sole inhabitant’s sadistic pleasure with an equal amount of non-sadistic pleasure instead, this might suggest the need for some minor tweaks to either hedonism or utilitarianism.9

The Experience Machine Objection

Robert Nozick disputed the view that happiness is the only basic good and suffering the only basic bad by providing a thought experiment intended to show that we value things other than conscious experiences. Specifically, Nozick argued that hedonists are committed, mistakenly, to plugging into an “experience machine”:

Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. It could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, pre-programming your life experiences?10

Nozick suggests that you should not plug into the experience machine, despite the machine promising a life filled with much more happiness than “real life”.11 Most of us do not merely want to passively experience “pre-programmed” sensations, however pleasant they might be; we also want to (i) make real choices, actively living our lives,12 and (ii) genuinely interact with others, sharing our lives with real friends and loved ones.13

If happiness were the only basic welfare good, it would not matter whether our experiences were real or were generated by the experience machine without any input from us (or others). Consequently, if we would prefer not to plug into the machine, that suggests we value things other than just happiness, such as autonomy and relationships.

One way that hedonists have tried to resist this argument is to question the reliability of the intuitions evoked by the thought experiment. In some cases, reluctance to plug into the machine might stem from pragmatic concerns that the technology may fail.14 Others might be moved by moral reasons to remain unplugged (for example, to help others in the real world), even if that means sacrificing their own happiness. Finally, many have argued that our responses to the thought experiment reflect status quo bias: if you tell people that they are already in the experience machine, they are much more likely to want to remain plugged in.15

Still, even after carefully bracketing these confounding factors, many will intuitively recoil from the suggestion that an experience machine could provide all that they truly want from life. Imagine that person A lives a happy and accomplished life in the real world, the subjective experience of which is somehow “recorded” and then “played back” to B (who is attached to an experience machine from birth), with just an extra jolt of mild pleasure at the end.16 Hedonism implies that B has the better life of the two, but many will find this implausible. Note that this intuition cannot so easily be explained away as stemming from pragmatic or moral confounds, or mere status-quo bias.

Roger Crisp advises hedonists to regard these intuitions as being useful rather than accurate:

This is to adopt a strategy similar to that developed by ‘two-level utilitarians’ in response to alleged counter-examples based on common-sense morality. The hedonist will point out the so-called ‘paradox of hedonism’, that pleasure is most effectively pursued indirectly. If I consciously try to maximize my own pleasure, I will be unable to immerse myself in those activities, such as reading or playing games, which do give pleasure. And if we believe that those activities are valuable independently of the pleasure we gain from engaging in them, then we shall probably gain more pleasure overall.17

Someone committed to hedonism on other grounds may thus remain untroubled by our intuitions about the experience machine. Even so, they raise a challenge for the view: if a competing theory yields intuitively more plausible verdicts, why not prefer that view instead? To adequately assess the prospects for hedonism, we must first explore the challenges for these rival accounts.

Desire Theories

We saw that hedonism struggles to capture all that people care about when reflecting on their lives. Desire theories avoid this problem by grounding well-being in each individual’s own desires.

Desire theories hold that well-being consists in the satisfaction (minus frustration) of desires or preferences.

According to desire theories, what makes your life go well for you is simply to get whatever it is that you want, desire, or prefer. Combining utilitarianism with a desire theory of well-being yields preference utilitarianism, according to which the right action best promotes (everyone’s) preferences overall.

Importantly, our preferences can be satisfied without our realizing it, so long as things in reality are as we prefer them to be. For example, many parents would prefer to:

(i) Falsely believe their child has died, when the child is actually alive and happy,

rather than to:

(ii) Falsely believe their child is alive and happy, when the child is actually dead.

A parent who strongly desires a happy life for their child may be happier in scenario (ii), where they (falsely) believe this desire to be satisfied. But their desire is actually satisfied in (i), and that is what really benefits them, according to standard desire theories.18

As a result, desire theories can easily account for our reluctance to plug into the experience machine.19 It offers happiness based on false beliefs. But if we care about anything outside of our own heads (as most of us seem to), then the experience machine will leave those desires unfulfilled. A “real” life may contain less happiness, but more desire-fulfillment, and hence more well-being according to desire theories.

Desire theories may be either restricted or unrestricted in scope. Unrestricted theories count all of your desires, without exception. On such a view, if you desire that our galaxy contains an even number of stars, then you are better off if this is true, and worse off if it is false. Restricted desire theories instead claim that only desires in some restricted class—perhaps those that are in some sense about your own life20—affect your well-being. Under a restricted theory, something can seem good to you without being good for you, and this kind of desire would not be seen as meaningfully affecting your well-being.

Desire theories may be motivated by the thought that what makes your life go well for you must ultimately be up to you. Other theorists might support anti-paternalistic policies in practice, supposing that individuals are typically the best judges of what is good for them,21 but only desire theorists take an individual’s preferences about their own life to determine what is good for them. By contrast, other theorists are more open to overruling an individual’s self-regarding preferences as misguided, if they fail to track what is objectively worthwhile.

Bizarre Desires

To test your intuitions about desire theories, it may help to imagine someone whose desires come apart from anything that is plausibly of objective value (including their own subjective happiness). Suppose that someone’s strongest desire is to count blades of grass, even though this is a compulsive desire that brings them no pleasure.22 Many of us would regard this preference as pathological, and worth overriding or even extinguishing for the subject’s own sake—at least if they would be happier as a result. But committed desire theorists will insist that, however strange another’s preferences may seem to us, it’s each person’s own preferences that matter for determining what is in their interests.23 How satisfying you find this response will likely depend on how strongly drawn to desire views you were in the first place.

Changing Preferences

One tricky question for desire theorists is how to deal with changing preferences. Suppose that, as a child, I unconditionally desire to be a firefighter when I grow up—that is, even in the event that my grown-up self wants a different career. Suppose that I will naturally develop to instead want to be a teacher, which would prove a more satisfying career for my adult self. But further suppose that, if I instead dropped out of school and became a drug addict, I would acquire stronger—and more easily satisfied—desires, although I currently view this prospect with distaste.24 Given these stipulations, am I best-off becoming a firefighter, a teacher, or a drug addict? Different desire theories will offer different answers to this question.

The simplest form of desire theory takes the well-being value of a life to be determined by the sum total of its satisfied desires minus its frustrated desires at each moment.25 Such a view could easily end up rating the prospect of drug addiction as providing the best future,26 no matter my current preferences.27 This would be an especially awkward implication for any who were drawn to desire views on the anti-paternalist grounds that each person gets to decide for themselves where their true interests lie.

To avoid this implication, one might decide to weigh present desires more heavily than potential future desires. A necessitarian approach, for example, only counts desires that exist (or previously existed) in all of the potential outcomes under consideration.28 This nicely rules out induced desires, as in the induced addiction scenario, but may also justify impeding natural desire change (such as between firefighting and teaching careers), which can seem counterintuitive.29 So it’s far from straightforward for desire theorists to give intuitive answers across a range of preference-change cases.

Objective List Theories

Both hedonism and desire theories are monist. They suggest that well-being consists of a single thing—either happiness or desire satisfaction. In contrast, while objective list theorists usually agree that happiness is an important component of well-being, they deny that it’s the only such component; consequently, objective list theories are pluralist.30

Objective list theories hold that there are a variety of objectively valuable things that contribute to one’s well-being.

In addition to happiness, these lists commonly include loving relationships, achievement, aesthetic appreciation, creativity, knowledge,31 and more. Crucially, these list items are understood as basic or intrinsic goods; they are valuable in themselves, not because of some instrumental benefit they provide. The list is called objective, because its items are purported to be good for you regardless of how you feel about them. The same list applies to everyone, though different lives may end up realizing different goods from the list, so there may still be many different ways of living an excellent life. On this view, some things (such as love and happiness) are inherently more worth caring about than others (such as counting blades of grass), and it makes your life go better if you attain more of the things that are truly good or worth pursuing.

Objective list theories do not necessarily imply that people would benefit from being forced to pursue objective goods against their will. Autonomy could be a value on the list, and happiness certainly is; either of these is apt to be severely thwarted by such coercion. Still, one notable implication is that if you are able to change someone’s preferences from worthless to worthwhile goals, this is likely to improve their well-being (even if they are no more satisfied, subjectively speaking, than before).

Objective list theories are thus in a good position to explain which preference-changes are good or bad for you (a potential advantage over desire theories). And the inclusion of values beyond just happiness yields more plausible verdicts than hedonism in “experience machine” cases.32

Is Objective Value “Spooky”?

Resistance to objective list theories may stem from the sense that there is something metaphysically extravagant, disreputable, or “spooky” about the objective values they posit—that they are a poor fit with a modern scientific worldview. But competing theories of well-being are arguably in no better position regarding such metaethical33 concerns. Well-being is an inherently evaluative concept: it is that which is worth pursuing for an individual’s sake.34 (If you are not describing something that matters in this way, then whatever it is that you are giving an account of, it cannot truly be well-being. A thoroughgoing nihilist must deny that there is any such thing.)35

Utilitarians, especially, regard well-being as objectively valuable: if someone claims that others’ interests do not matter, we think they are making a serious moral mistake. So we’re already committed to moral facts that hold regardless of others’ opinions. So what further cost is there to claiming that something may contribute to another’s well-being regardless of their feelings or opinions? (In the ‘Alienation’ section below, we consider the objection that this yields implausible verdicts. But for now, we’re just considering the objection that there would be something “spooky” or unscientific about it.) Once you are on board with welfare value at all, it’s not clear that there is any additional metaphysical cost to accepting an objective list theory in particular.36

On the other hand, it can be hard to shake the sense that there is something less mysterious-seeming about grounding value in what we want or what makes us happy. The challenge for the critic here is to develop an argument that makes clear what metaphysical difference follows from grounding value in our desires or feelings, so long as the resulting value is equally real and important no matter what it’s grounded in. Otherwise, the intuitive force of the “spookiness” objection may just stem from mistakenly conflating feeling-based value with outright nihilism.37

A related (but importantly different) argument might start from the idea that there should be some common explanation available for why the things on the objective list are good. Some critics may find objective list theories arbitrary or ad hoc, in contrast to hedonism and desire theories which each offer a way to unify all welfare goods into a single kind (either happiness or desire satisfaction). Objective list theorists may respond by disputing the idea that any such common explanation is necessary: Why could there not be several different kinds of things that can each enrich one’s life in fundamentally different ways? (And why regard a list with just one item on it—whether happiness or desire satisfaction—as any less arbitrary?)38 Whether or not you are inclined to assume that a “common explanation” is necessary (or even to be expected) here may thus have a significant impact on how plausible you find objective list theories.

Alienation

Perhaps the most powerful objection to objective list theories instead challenges it on its putative point of strength: its ability to accommodate our intuitive judgments about what makes one’s life go well. If we imagine a subjectively miserable life, it’s hard to believe that it could be a really good life for the person living it, no matter how highly they might score on all the other putative objective values (besides happiness). Someone who feels deeply alienated from the putative “goods” in their life would not seem to benefit from the goods in question.39 A committed hermit, for example, might deny that having friends to interrupt his solitude would do him any good at all. So this casts doubt on the simple objective list theory that takes the items on the list to constitute welfare goods regardless of whether we want them or they make us happy.

This concern might move us towards a hybrid view, according to which well-being consists in subjective appreciation of the objective candidate welfare goods.40 So unwanted friendships no longer count as a “benefit” to the hermit. But if he came to truly appreciate other people, this would be better for him than getting equal enjoyment from merely counting blades of grass. In this way, the alienation objection can be addressed while (i) rejecting the experience machine and (ii) maintaining the core objectivist idea that some ways of life are better for us than others, even if they would result in equal desire satisfaction and happiness.

Practical Implications of Theories of Well-Being

Hedonism, desire theories, and objective list theories of well-being all largely overlap in practice. This is because we tend to desire things that are (typically regarded as) objectively worthwhile, and we tend to be happier when we achieve what we desire. We may also tend to reshape our desires based on our experiences of what feels good. As a result, defenders of any given theory of well-being might seek to debunk their competitors by suggesting that competing values (be they pleasure, desire-fulfillment, or objective goods) are of merely instrumental value, tending to produce, or otherwise go along with, what really matters.

Still, by appealing to stylized thought experiments (involving experience machines, changing preferences, and the like), we can carefully pry apart the implications of the various theories of well-being, and so form a considered judgment about which theory strikes us as most plausible.

Even if the theories currently coincide in practice, their differences could become more practically significant as technology advances, and with it, our ability to manipulate our own minds. If we one day face the prospect of engineering our descendants so that they experience bliss in total passivity, it will be important to determine whether we would thereby be doing them a favor, or robbing them of much of what makes for a truly flourishing life.

Conclusion

While utilitarians agree about wanting to promote well-being, they may disagree about what constitutes well-being: what things are basic goods and bads for us. According to the most prominent theories of well-being, it may consist of either happiness, desire satisfaction, or a plurality of objective goods.

Hedonism, in holding happiness to be the only basic welfare good, achieves simplicity at the cost of counterintuitive implications in the experience machine thought experiment.

Desire theories avoid these implications, but risk other counterintuitive implications in cases involving bizarre or changing desires.

Finally, objective list theories risk alienating individuals from their own welfare goods, unless some concessions are made towards what the individual desires or what makes them happy. As a result, a more complex hybrid account may do the best job of capturing our myriad intuitions about well-being.

The competing theories of well-being mostly coincide in practice, but this may change as technology advances. Their implications may differ starkly in scenarios involving futuristic technology such as digital minds and virtual reality. Whether the future we build for our descendants is utopian or dystopian may ultimately depend on which theory of well-being is correct—and whether we can identify it in time.

The next chapter discusses population ethics, and how to evaluate outcomes in which different numbers of people may exist.

How to Cite This Page

Resources and Further Reading

Introduction

- Roger Crisp (2017). Well-Being. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Shelly Kagan (1992). The Limits of Well-being. Social Philosophy & Policy. 9(2): 169–189.

- Eden Lin (2022). Well‐being, part 1: The concept of well‐being. Philosophy Compass. 17(2).

- Eden Lin (2022). Well‐being, part 2: Theories of well‐being. Philosophy Compass. 17(2).

- Derek Parfit (1984). Appendix I: What Makes Someone’s Life Go Best, Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Welfarism

- Nils Holtug (2003). Welfarism – The Very Idea. Utilitas. 15(2): 151–174.

- Andrew Moore & Roger Crisp (1996). Welfarism in moral theory. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 74(4): 598–613.

Hedonism

- Andrew Moore (2019). Hedonism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Ole Martin Moen (2016). An Argument for Hedonism. The Journal of Value Inquiry. 50: 267–281 (2016).

- Ivar Labukt (2012). Hedonic Tone and the Heterogeneity of Pleasure. Utilitas. 24(2): 172–199.

- Roger Crisp (2006). Hedonism Reconsidered. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 73(3): 619–645.

- Fred Feldman (2004). Pleasure and the Good Life: Concerning the Nature Varieties and Plausibility of Hedonism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Desire Theories

- Chris Heathwood (2015). Desire-fulfillment theory, in Guy Fletcher (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Well-Being. London: Routledge.

- Peter Singer (2011). Chapter 1: About Ethics, in Practical Ethics (3rd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chris Heathwood (2006). Desire Satisfactionism and Hedonism. Philosophical Studies. 128: 539–563.

- Mark Murphy (2002). The Simple Desire‐Fulfillment Theory. Noûs. 33(2): 247–272.

- Wlodek Rabinowicz & Jan Österberg (1996). Value Based on Preferences: On Two Interpretations of Preference Utilitarianism. Economics and Philosophy. 12(1): 1–27.

Objective List Theories

- Guy Fletcher (2013). A Fresh Start for an Objective List Theory of Well-Being. Utilitas. 25(2): 206–220.

- James Griffin (1986). Well-Being: Its Meaning, Measurement and Moral Importance. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Eden Lin (2014). Pluralism about Well-Being. Philosophical Perspectives. 28(1): 127–154.

Théorie des peines et des récompenses (1811); translation by Richard Smith, The Rationale of Reward, J. & H. L. Hunt, London, 1825, book 3, chapter 1. ↩︎

For a more detailed overview of theories of well-being, see Crisp, R. (2017). Well-Being. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Section 4: Theories of Well-being. ↩︎

This tripartite classification is widespread in the literature—following Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons, Appendix I: ‘What Makes Someone’s Life Go Best’. It has, however, been criticized: cf. Woodard, C. (2013). Classifying theories of welfare. Philosophical Studies, 165: 787–803. ↩︎

For a more detailed account of and discussion of hedonism, see Moore, A. (2019). Hedonism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). ↩︎

Hedonism about well-being should not be confused with psychological hedonism, the dubious empirical claim that humans always pursue what will give themselves the greatest happiness. ↩︎

This view is known as ethical egoism. ↩︎

Cf. Sinhababu, N. (ms). The Epistemic Argument for Hedonism, and his guest essay, Naturalistic Arguments for Ethical Hedonism. ↩︎

To control for this, imagine a society of utilitarian sadists who are strictly morally constrained in their sadism: they would never allow harm to another unless it caused greater net benefits to others (including themselves). We might even imagine that they are willing to suffer the torture themselves if enough others would benefit from this. (Perhaps they draw lots to decide on a victim, in a sadistic analogue of John Harris’ Survival Lottery.) When the sadists are stipulated to be morally conscientious in this way, it may be easier to accept that their sadistic pleasure counts as a good in itself.

Harris, J. (1975). The Survival Lottery. Philosophy 50: 81–87. ↩︎

Unless we value the simplicity of hedonistic utilitarianism more highly than the accommodation of such intuitions. ↩︎

This description was adapted from Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books, p. 42. ↩︎

Of course, one might agree with Nozick’s general point while regarding life in the experience machine as superior to at least some (e.g. miserable) “real” lives, such that “plugging in” could be advisable in some circumstances. ↩︎

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books, p. 43. ↩︎

Nozick further claimed that we want to live “in contact with reality”, but it’s not clear that there would be any loss of well-being in living and interacting with others in a shared virtual world like that depicted in The Matrix. A shared virtual world could, in contrast to the experience machine, fulfill many of our non-hedonic values and desires, such as having friends and loving relationships.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books, p. 45. ↩︎

Weijers, D. (2014). Nozick’s experience machine is dead, long live the experience machine! Philosophical Psychology. 27(4): 513–535. Puzzlingly, many respondents reported that they would favor plugging in to the experience machine when choosing for another person, even when they would not choose this for themselves. ↩︎

Among others, this suggestion has been made by:

Kolber, A. (1994). Mental Statism and the Experience Machine. Bard Journal of Social Sciences. 3: 10–17.

Greene, J. D. (2001). A Psychological Perspective on Nozick’s Experience Machine and Parfit’s Repugnant Conclusion. Presentation at the Society for Philosophy and Psychology Annual Meeting. Cincinnati, OH.

de Brigard, F. (2010). If you like it, does it matter if it’s real?. Philosophical Psychology. 23(1): 43–57. ↩︎

Adapted from Crisp, R. (2006). Hedonism Reconsidered. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 73(3): 635–6.

The advantages of third-personal judgments about the relative values of lives inside and outside of the experience machine, to better avoid objections, is also stressed by Lin, Eden (2016). How to Use the Experience Machine. Utilitas 28 (3):314-332. ↩︎

Crisp, R. (2017). Well-Being. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Section 4.1 Hedonism. See also Crisp, R. (2006). Hedonism Reconsidered. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 73(3): 637. ↩︎

They probably also desire their own happiness, of course, which is better served in scenario (ii). But the fact that they nonetheless prefer the prospect of (i) over (ii) suggests that (i) is the outcome that better fulfills their desires overall. ↩︎

By contrast, the “evil pleasures” objection to hedonism would seem to apply with equal force against desire theories, as these theories also imply that sadistic pleasure can benefit you (if you desire it). ↩︎

This is Parfit’s suggestion in Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press. For an alternative restriction based on genuine attraction, see Heathwood, C. (2019). Which Desires are Relevant to Well-Being?. Noûs. 53(3): 664–688. ↩︎

As argued by John Stuart Mill in his 1859 book On Liberty. ↩︎

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press, p. 432.

Some desire theorists might restrict their view to ‘hot’ desires, that present their objects as being in some way appealing to the subject, in contrast to mere compulsive motivations. But the counterexample can be adapted to cover the ‘hot’ desire view as follows: Further suppose that the agent suffers from severe memory loss, so they don’t even appreciate when this desire is satisfied. Still, it is what they want to happen, so much so that they would prefer to count grass (without realizing it) than to pause to take medicine that would restore their cognitive functioning and ability to enjoy themselves (without generating stronger new desires). Again, this preference seems pathological, and worth overriding for the subject’s sake. ↩︎

Chris Heathwood additionally stresses the importance of looking at the agent’s overall (whole-life) desire satisfaction. Sometimes it will be worth thwarting one desire in order to better promote others. But we can build into the case that the person’s actual desires are maximally satisfied by leaving them to forgetfully count the grass.

Heathwood, C. (2005). The problem of defective desires. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 83 (4): 487–504. ↩︎

Adapted from Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 497. Parfit stipulates that the agent is guaranteed a lifetime supply of the drug, and that the drug in question poses no health risk or untoward side-effects besides the extreme addiction. ↩︎

Weighted by how strong each desire is. For example, you may be well off overall if you have one very strong desire satisfied, and two very weak ones frustrated. ↩︎

That is, the best future in terms of this one individual’s well-being. They might still have moral reasons to choose a different future, as being a teacher or firefighter would surely help others more. But even the limited claim that drug addiction is what is best for this individual will seem counterintuitive to many. ↩︎

One’s past desires to avoid this outcome would weigh against it to some degree, unless one builds in a “concurrence requirement” that only desires existing at the same time as their satisfaction count. Concurrence views thus have even more difficulty avoiding the implication that such induced desire satisfactions can easily override your present preferences. ↩︎

This theory is temporally relative because once the relevant choice is made, the once-contingent future choice may no longer be contingent on any remaining decisions, in which case it will no longer be discounted. If you actually become a satisfied drug addict, for example, the necessitarian may now say that this outcome was for the best, even though before the choice was made, they would have advised against it (on the basis of your prior desires). This generates an awkward temporal inconsistency, as our theorist seems committed to claims like, “It would now be bad for you to become a drug addict, but if you go ahead and do it, it will instead be good for you.” ↩︎

It merely “may” because much depends on the details. It’s entirely possible that becoming a well-satisfied teacher would also better serve other desires that one has (in both outcomes). In which case, even the necessitarian could conclude that this change would be in one’s overall best interests, despite giving no intrinsic weight to the contingent desire to be a teacher (and giving full weight to the past, and hence non-contingent, desire to be a firefighter). But there will be at least some cases in which impeding the change counterintuitively wins out because of the discounting. ↩︎

Objective list theorists include: Finnis, J. (1980). Natural Law and Natural Rights. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Griffin, J. (1986). Well-Being: Its Meaning, Measurement and Moral Importance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Fletcher, G. (2013). A Fresh Start for an Objective List Theory of Well-Being. Utilitas. 25(2): 206–220. Lin, E. (2014). Pluralism about Well-Being. Philosophical Perspectives. 28(1): 127–154.

For an overview and discussion of value pluralism, including objective list theories, see: Mason, E. (2018). Value Pluralism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Lin, E. (2016). Monism and Pluralism. In Guy Fletcher (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Well-Being. Routledge, pp. 331–41. ↩︎

Though there would not seem any value in memorizing the phonebook or other trivial data, so this is best restricted to significant knowledge, or knowledge of important truths. ↩︎

Recall our contrast of person A (with the excellent life) and person B who experiences a passive “replay” of A’s life, with an extra jolt of pleasure at the end. Although B’s life contains more pleasure, A’s life will contain more overall value if we also count loving relationships, achievement, etc., as basic welfare goods. While B’s life contains all the same experiences as of loving relationships, achievement, etc., as A’s did, it is a passive “replay”, involving no actual choices or interactions. Therefore, B’s life includes none of A’s actual achievements or relationships. ↩︎

For a state of the art exploration of the relations between theories of well-being and metaethical views, see Fletcher, G. (2021). Dear Prudence: The Nature and Normativity of Prudential Discourse. Oxford University Press. Chapter 7: Prudential Normativity. ↩︎

Note that to be worth pursuing for an individual’s sake does not entail being worth pursuing all things considered. It’s more of a conditional reason: insofar as you have reason to care about S’s well-being, you have reason to care about what is desirable, or worth pursuing, for S’s sake. Utilitarians think we always have reason to care about everyone’s well-being. But others may disagree. So it remains an open conceptual possibility that you should not care about someone’s well-being. If you think that S deserves to be punished, for example, you may see what is undesirable for S’s sake as being all things considered desirable, precisely because it is bad for S. ↩︎

Expressivists may give an anti-realist gloss on what “really mattering” amounts to. But then they can just as comfortably extend this gloss to the kind of first-order “objectivity” posited by objective list theories. ↩︎

Cf. Bedke, M. (2010). Might All Normativity be Queer?. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 88(1): 41–58. ↩︎

It would indeed be less “mysterious” to deny the reality of value, and claim that subjective valuing is all there is in the vicinity. But this would be a form of nihilism: that S values p is a purely descriptive fact about S’s psychology. There is nothing inherently value-laden about this, unless we further claim that subjective valuation is something that actually matters in some way. And then we are back to attributing real value, in all its mysterious glory. ↩︎

One advantage of only having one good on the list is that you avoid potential arbitrariness in exchange rates (between the different types of goods). But that’s different from claiming that there’s arbitrariness in which things get to count as good at all. ↩︎

As Peter Railton writes: “what is intrinsically valuable for a person must have a connection with what he would find in some degree compelling or attractive, at least if he were rational and aware. It would be an intolerably alienated conception of someone’s good to imagine that it might fail in any such way to engage him.”

Railton, P. (2003). “Facts and Values”, in Facts, Values and Norms. Cambridge University Press, p. 47. ↩︎

Perhaps the best-known such hybrid view is found in Kagan, Shelly (2009). Well-Being as Enjoying the Good. Philosophical Perspectives 23 (1):253-272. ↩︎