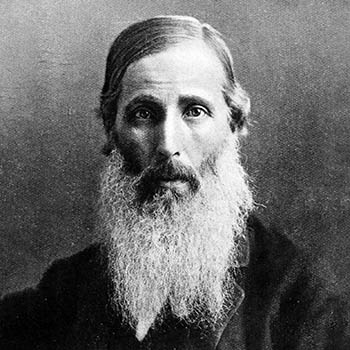

Sidgwick was born in 1838 to a wealthy family in Yorkshire, England. He studied at Cambridge as an undergraduate, where he stayed for the rest of his life. While he is best known as a moral philosopher, he was also a political economist, epistemologist, classicist, theologist, educator, political theorist and parapsychologist (studying psychic phenomena, including telepathy and survival after death).1 At Cambridge, Sidgwick became a part of “the Apostles”: a secret society whose members discussed topics including ethics, truth and God. He married Eleanor Mildred Balfour, a scientist with whom he advocated to expand higher education for women and conducted parapsychological research.

Sidgwick is best known for writing The Methods of Ethics, an overview of utilitarianism and its historical alternatives, and their relation to ordinary moral reasoning. According to John Rawls, Sidgwick’s Methods of Ethics “is the clearest and most accessible formulation of… ‘the classical utilitarian doctrine’”,2 and, according to J. J. C. Smart it is “the best book ever written on ethics”.3 Not only was this a valuable formulation and justification of classical utilitarianism, it also proved to be a model for the study of ethics more generally. The book can be seen partly as an exposition, systematization and correction of commonsense morality. In it, Sidgwick outlined three approaches to ethics: intuitionism, egoism and utilitarianism, and attempted to reconcile them with each other. While he doubted that egoism and utilitarianism could be reconciled (in what he termed the “dualism of practical reason”), he argued that fundamental utilitarian axioms and intuitionism could be. This insight proved vital in the popularization of utilitarianism in the 20th century.

Sidgwick was also a committed social reformer. His primary interest was the expansion of women’s higher education, and he founded Newnham College, Cambridge, for this purpose. He supported the secularization of education, and (temporarily) resigned from his fellowship at Cambridge University in 1869 when he could no longer subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England. He also supported poor relief, and, as a political economist, challenged the doctrine of laissez-faire.4

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Representative Works of Henry Sidgwick

- The Methods of Ethics (London, 1874)

- The Principles of Political Economy (London, 1883)

- The Elements of Politics (London, 1891)

Resources on Henry Sidgwick’s Life and Work

- Schultz, B. (2019). Henry Sidgwick. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.).

- Singer, P. & de Lazari-Radek, K. (2014). The Point of View of the Universe: Sidgwick and Contemporary Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Singer, P. (2011). Henry Sidgwick’s Ethics. Philosophy Bites Podcast.

Prominent Quotes of Henry Sidgwick

- “the good of any one person is no more important from the point of view (if I may put it like this) of the universe than the good of any other; unless there are special grounds for believing that more good is likely to occur in the one case than in the other.”5

- “Who are the ‘all’ whose happiness is to be taken into account? Should our concern extend to all the beings capable of pleasure and pain whose feelings we can affect? Or should we confine our view to human happiness? Bentham and Mill adopt the former view, as do (I believe) utilitarians generally; and it is obviously more in accordance with the universality of their principle. A utilitarian thinks it is his duty to aim at the good universal… interpreted and defined as ‘happiness ‘or ‘pleasure’; and it seems arbitrary to exclude from this project any pleasure of any sentient being.”6

- “We think of a philosopher as trying to do more than merely define and formulate the common moral opinions of mankind. His function is to tell men not what they do think but what they ought to think; he is expected to go beyond common sense in his premises, and is allowed some divergence from it in his conclusions… his task is to state in full strength and clarity the primary intuitions of reason which can, handled scientifically, systematise and correct the common moral thought of mankind.”7

Schultz, B. (2019). Henry Sidgwick. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.). ↩︎

Sidgwick, H. (1981). Methods of Ethics. 7th edn., Hackett Publishing Co. ↩︎

Smart, J. J. C. (1956). Extreme and Restricted Utilitarianism. The Philosophical Quarterly. 6(25): 344–354, p. 347. ↩︎

Schultz, B. (2019). Henry Sidgwick. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.). ↩︎

The Methods of Ethics, 1884, p. 186 ↩︎

The Methods of Ethics, 1884, p. 201 ↩︎

The Methods of Ethics, 1884, p. 182 ↩︎