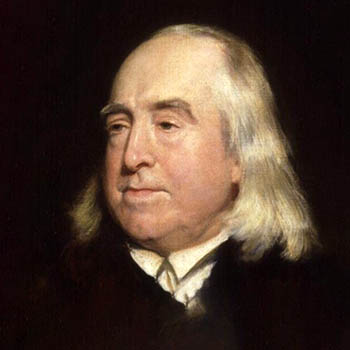

Jeremy Bentham was born in 1748 to a wealthy family. A child prodigy, his father sent him to study at Queen’s College, Oxford University, aged 12. Although he never practiced, Bentham trained as a lawyer and wrote extensively on law and legal reform. He died in 1832 at the age of 84 and requested his body and head to be preserved for scientific research. They are currently on display at University College London.

Jeremy Bentham is often regarded as the founder of classical utilitarianism. According to Bentham himself, it was in 1769 he came upon “the principle of utility”, inspired by the writings of Hume, Priestley, Helvétius and Beccaria.1 This is the principle at the foundation of utilitarian ethics, as it states that any action is right insofar as it increases happiness, and wrong insofar as it increases pain. For Bentham, happiness simply meant pleasure and the absence of pain and could be quantified according to its intensity and duration. Famously, he rejected the idea of inalienable natural rights—rights that exist independent of their enforcement by any government—as “nonsense on stilts”.2 Instead, the application of the principle of utility to law and government guided Bentham’s views on legal rights. During his lifetime, he attempted to create a “utilitarian pannomion”—a complete body of law based on the utility principle. He enjoyed several modest successes in law reform during his lifetime (as early as 1843, the Scottish historian John Hill Burton was able to trace twenty-six legal reforms to Bentham’s arguments)3 and continued to exercise considerable influence on British public life.

Many of Bentham’s views were considered radical in Georgian and Victorian Britain. His manuscripts on homosexuality were so liberal that his editor hid them from the public after his death.4 Underlying his position on the decriminalization of homosexuality were his beliefs that the right end of government is the maximization of happiness, and that the severity of punishment should be proportional to the harm inflicted by the crime. He was also an early advocate of animal welfare, famously stating that their capacity to feel suffering gives us reason to care for their well-being: “The question is not can they reason? Nor, can they talk? But can they suffer?”.5 As well as animal welfare and the decriminalization of homosexuality, Bentham supported women’s rights (including the right to divorce), the abolition of slavery, the abolition of capital punishment, the abolition of corporal punishment, prison reform and economic liberalization.6

Bentham also applied the principle of utility to the reform of political institutions. Believing that with greater education, people can more accurately discern their long-term interests, and seeing progress in education within his own society, he supported democratic reforms such as the extension of the suffrage. He also advocated for greater freedom of speech, transparency and publicity of officials as accountability mechanisms. A committed atheist, he argued in favor of the separation of church and state.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Representative Works of Jeremy Bentham

- A Fragment on Government (London, 1776)

- An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (London, 1789)

- Deontology (London, 1834)

Resources on Jeremy Bentham’s Life and Work

- Who was Jeremy Bentham? The Bentham Project, University College London.

- Crimmins, J. E. (2019). Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.).

- Sweet, W. Jeremy Bentham. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Schofield, P. (2012). Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism. Philosophy Bites Podcast.

- Gustafsson, J. E. (2018). “Bentham’s Binary Form of Maximizing Utilitarianism”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 26 (1): 87–109.

Prominent Quotes of Jeremy Bentham

- “[T]he dictates of utility are just the dictates of the most extensive and enlightened—i.e.well-advised—benevolence”.7

- “The principle of utility judges any action to be right by the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interests are in question.”8

- “Create all the happiness you are able to create: remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you to add something to the pleasure of others, or to diminish something of their pains.” (Bentham’s advice to a young girl, 1830)

- “The day may come when the non-human part of the animal creation will acquire the rights that never could have been withheld from them except by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the whims of a tormentor. Perhaps it will some day be recognised that the number of legs, the hairiness of the skin, or the possession of a tail, are equally insufficient reasons for abandoning to the same fate a creature that can feel? What else could be used to draw the line? Is it the faculty of reason or the possession of language? But a full-grown horse or dog is incomparably more rational and conversable than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month old. Even if that were not so, what difference would that make? The question is not Can they reason? Or Can they talk? but Can they suffer.”9

Cf. Bentham, J. (1821). On the Liberty of the Press, and Public Discussion. and Crimmins, J. E. (2019). Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.). ↩︎

Bentham, J. (1843). Anarchical Fallacies. ↩︎

Alfange, D. J. (1969). Jeremy Bentham and the Codification of Law. Cornell Law Review. 55(1): 58–77, p. 76 ↩︎

Cf. Dabhoiwala, F. (2014). Of Sexual Irregularities by Jeremy Bentham – review. The Guardian. ↩︎

Bentham, J. (1789). An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Bennett, J. (ed.), pp. 143–144 ↩︎

Cf. Bentham, J. (1821). On the Liberty of the Press, and Public Discussion. and Crimmins, J. E. (2019). Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.). ↩︎

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789, p. 68 ↩︎

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789 ↩︎

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789, p. 144 ↩︎