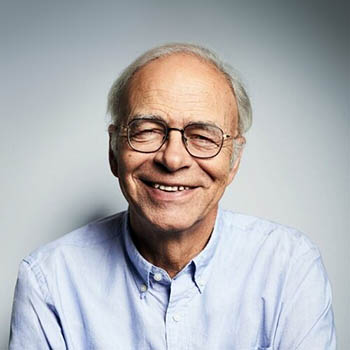

Singer was born in 1946, Melbourne, Australia, to an Austrian Jewish family that emigrated from Austria to escape persecution by the Nazis. He studied law, history and philosophy at the University of Melbourne, and majored in philosophy. He later did a B.Phil at Oxford University, where he associated with a vegetarian student group and became a vegetarian himself. Around this time he wrote Animal Liberation (1975), which has been called the “bible” of the animal liberation movement.1

In 1999, Singer was appointed as Professor of Bioethics in the University Center for Human Values at Princeton. In 2004, he was recognized as the Australian Humanist of the Year by the Council of Australian Humanist Societies. He founded the non-profit organisation The Life You Can Save, named after his book of the same name, and is often regarded as a core intellectual inspiration to the effective altruism movement.2 Singer is the most famous and influential contemporary utilitarian philosopher.

Singer is best known for his views on animal ethics. In his book Animal Liberation he popularized the term speciesism, which he defines as “a prejudice or attitude of bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of members of other species”.3 He argues for the equal consideration of human and non-human animal interests because animals have the capacity for suffering and enjoyment. He rejects the idea that non-human animals’ interests should be considered less based on their intelligence with the argument from marginal cases: if we should consider the interests of infants, the cognitively disabled and the senile equally to the interests of the average human, we should also consider the interests of non-human animals equally, for there is no relevant property these humans have that non-human animals lack. Consequently, Singer has long advocated for reducing the suffering of farmed animals.

Singer has also campaigned against global poverty. In 1972, he wrote a widely-cited article titled Famine, Affluence and Morality in which he introduces the famous “drowning child” thought experiment.4 The principle underlying it is that if one can save a life sacrificing nothing of moral significance, one has an obligation to do so. The implication of this principle is that people in rich countries have an obligation to give up at least some of their income to help the poor, insofar as it is possible. Singer has also argued that affluent nations ought to take much stronger action on climate change, and has argued in favor of the legalization of abortion and the legality of euthanasia.5

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Representative Works of Peter Singer

- Famine, Affluence and Morality (1972)

- Animal Liberation (New York, 1975)

- Practical Ethics (Cambridge, 1979)

- The Life You Can Save (2019) (available for free download)

Resources on Peter Singer’s Life and Work

Prominent Quotes of Peter Singer

- “Living a minimally acceptable ethical life involves using a substantial part of our spare resources to make the world a better place. Living a fully ethical life involves doing the most good we can.”6

- “The only justifiable stopping place for the expansion of altruism is the point at which all whose welfare can be affected by our actions are included within the circle of altruism. This means that all beings with the capacity to feel pleasure or pain should be included; we can improve their welfare by increasing their pleasures and diminishing their pains.”7

- “Racists violate the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race when there is a clash between their interests and the interests of those of another race. Sexists violate the principle of equality by favoring the interests of their own sex. Similarly, speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species. The pattern is identical in each case.”8

- “When we buy new clothes not to keep ourselves warm but to look “well-dressed” we are not providing for any important need. We would not be sacrificing anything significant if we were to continue to wear our old clothes, and give the money to famine relief. By doing so, we would be preventing another person from starving. It follows from what I have said earlier that we ought to give money away, rather than spend it on clothes which we do not need to keep us warm. To do so is not charitable, or generous. Nor is it the kind of act which philosophers and theologians have called “supererogatory” - an act which it would be good to do, but not wrong not to do. On the contrary, we ought to give the money away, and it is wrong not to do so.”9

Villanueva, G. (2016). ‘The Bible’ of the animal movement: Peter Singer and animal liberation, 1970–1976. History Australia. 13(3): 399–414, p. 399. ↩︎

In 2013, Peter Singer gave a TED talk on effective altruism. For a more detailed and recent introduction to effective altruism, see William MacAskill (2019). Effective Altruism. The Norton Introduction to Ethics, Elizabeth Harman & Alex Guerrero (eds.). ↩︎

Singer, P. (2002). Animal Liberation. New York: HarperCollins, p. 6. ↩︎

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence and Morality. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1(3): 229–243. ↩︎

Cf. Singer, P. (2011). Practical Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

The Most Good You Can Do, 2015, Preface. ↩︎

The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution, and Moral Progress, 1981. ↩︎

Animal Liberation, 2002, p. 9. ↩︎

Famine, Affluence and Morality, 1972. ↩︎