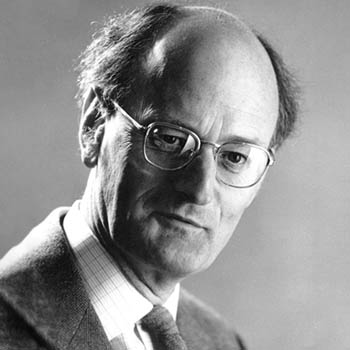

Richard M. Hare (1919 - 2002) is usually acknowledged to be one of the major moral thinkers of the 20th century. After being a Japanese prisoner of war for most of World War II, he completed his education at Oxford, later joining the faculty and becoming a professor. In 1983 he moved to the University of Florida but still kept his ties with Oxford. He had many students, including Peter Singer. At a memorial service for Hare in 2002, Singer ascribed to him three major achievements in moral philosophy, namely “restoring reason to moral argument, distinguishing intuitive and critical levels of moral thinking, and pioneering the development of practical or applied ethics”.1

Over his career, Hare tried to show how moral reasoning could be rational and differ from other kinds of reasoning. He began with an analysis of moral language, asking: What do we mean when we say “You ought to do X” in a moral sense? There are various interpretations of statements like this, and many are not moral, for instance, “If you want to rob the bank, you ought to plan your getaway carefully”. Hare emphasised that if we want to discuss morality and argue about it, we need to know what we are talking about. Or, as Wittgenstein wrote, “Whereof we cannot speak, we must remain silent”.2 Moreover, we often use moral concepts in our daily lives. Why would we rely on these concepts if they had no force? In fact, moral concepts are used to convey a category of social norms. This category may be only a few millennia old, and it may have been conflated together with concepts of social convention and etiquette. Nevertheless, it is one that modern people use a lot, and it is the topic of interest for Hare.

As Hare’s work developed, he argued more strongly that moral thinking, correctly done, would lead to utilitarianism. By arguing that such thinking could be evaluated by criteria of rationality, he departed from other popular philosophical views while at the same time trying to preserve what was valuable about each one. Surprisingly, the view he felt was closest to his own was that of Immanuel Kant. This was despite the fact that Hare thought that Kant’s categorical imperative was vaguely stated and that Kant’s examples were misleading and distorted by Kant’s moral intuitions, which came from his religious upbringing. Moreover, Hare believed, roughly, that the interpretation of the categorical imperative in terms of avoiding self-contradiction (as in the case of lying) covers too few cases and that the idea of “willing a maxim to be a universal law” includes evaluation of the psychological states of those affected by the maxim. However, Hare believed that the categorical imperative would lead to utilitarian conclusions when interpreted more broadly, without the baggage of Kant’s examples and with some of the ambiguities resolved.

By contrast, Hare rejected several other views, including naturalism, the idea that morality is based on natural law. Naturalism implies that statements about morality are just statements about matters of fact and can, in principle, be argued about and resolved the same way. While this view, to its credit, avoids moral relativism, it misses an important difference between statements such as “slavery is wrong” and “slavery barely exists anymore”. Namely, while the latter is a factual statement, the former is a recommendation. Thus, Hare rejected naturalism because it commits the “naturalistic fallacy” of trying to derive “ought” from “is”.

Hare also rejected reliance on emotivism, the claim that a statement like “abortion is wrong” merely amounts to “abortion, boooh… and I would like you to feel the same way”. Emotivism avoids the pitfalls of naturalism, but it leads to relativism: each of us has our own answers to what is right and wrong, and we have no way to reason about our differences. While Hare deemed relativism unacceptable, he believed the emotivist idea that moral judgments have something to do with emotions and preferences is worth saving.

Similarly, Hare rejected reliance on moral intuitions, even when attempts are made to systematize them by “reflective equilibrium”. Hare thought that while such an intuition-based enterprise can lead to a psychological account of our intuitions, it would not be a normative account. For Hare, even the reflective equilibrium could be unacceptably culturally relative—since much of our moral intuitions are specific to the culture we have grown up in. Hare’s last major book, Moral Thinking (1981), deals largely with the nature of moral intuitions.

With that out of the way, Hare sought to solve the problem of how to think and argue rationally about morality differently from thinking about matters of fact. The main element of Hare’s solution to this problem is his claim that moral statements are prescriptive; that is, they say something about what to do. In that regard, they are like imperative statements such as “shut the window”.

Importantly, prescriptive statements are subject to logical analysis. The logic of these statements holds, for example, that we cannot derive a prescriptive conclusion without a prescriptive premise in the syllogism. For instance, consider the statement, “Stop it from raining into the house; shutting the window is the only way to stop it from raining into the house; therefore, shut the window”. While you would not actually say this, the logic works.

In addition to being prescriptive, Hare believed that moral statements—such as “slavery is wrong”—are universal, thus bringing his analysis closer to Kant’s. Without qualification or conditions, the previous statement means that slavery is always wrong. Moral statements are like necessary statements about matters of fact, such as “Prime numbers other than three are not divisible by three”. This means “never”, in contrast to “It is possible that a rational number is divisible by three”, which is a statement of possibility, not necessity. The idea of universality is also present in Kant’s categorical imperative. If you say that it is wrong, in the moral sense, for me to break a particular promise to you, but not for you to break that particular promise to me (or anyone) in exactly the same situation (except that our roles are reversed), then something is wrong with your reasoning.

Consequently, Hare’s view is called universal prescriptivism. The property of universality in particular does a lot of work in Hare’s arguments.

Another major contribution of Hare’s is the idea of two levels of moral thinking, which first appeared in Freedom and Reason (1963, section 3.6) but was fully developed in Moral Thinking (1981).

Many common criticisms of utilitarianism concern its conflict with moral intuitions. Many of these intuitions, in turn, involve hypothetical examples, such as the much-studied footbridge case invented by Philippa Foot, in which your choice is whether to push a fat man off of a footbridge to stop a runaway trolley that would kill five people if not stopped.3 Of course, many of our intuitions concern real-world issues rather than philosophers’ thought experiments. For example, some people’s intuition says that killing innocent people is always wrong or that torture should be completely prohibited even if a general policy that permitted it under certain conditions would save many lives. Yet, since intuitions differ from person to person, it is hard to agree on the right action or policy, whether in hypothetical or real cases. Hare seeks to answer how people could argue about such moral disputes.

To this end, Hare argues that we have two levels of moral thinking, intuitive and critical. The critical level follows universal prescriptivism. The intuitive level provides us with principles that we may follow in our daily lives, such as not stealing or breaking promises. Presumably, Hare regards some intuitive principles as absolute while others are prima facie, to be overridden in case of conflict with other rules or considerations. Most intuitive principles are simple and easy to (try to) follow, and they are the source of our moral intuitions.

Importantly, Hare claims that we learn many of these rules from our culture and that they have evolved to be reasonably consistent with universal prescriptivism. Out of intellectual humility alone, it is wise to follow the rules we have been taught most of the time, even when we think we should not. (J. S. Mill made similar arguments in On Liberty for conclusions like the priority of free speech.) One of Hare’s examples is adultery. Too many people might be tempted, he argues, to follow the example in Lady Chatterly’s Lover, convincing themselves that adultery is consistent with the greater good, while distorting their factual beliefs , so that they are actually wrong. Instead, Hare believes it is best to follow the intuitive principle not to engage in adultery. Thus, Hare himself, along with Sidgwick, is on the “conservative” side of this issue, putting considerable trust in the intuitive rules that a good upbringing would instill, and arguing that moral education should teach people the useful rules. Other utilitarians, such as Bentham, Mill and Singer, have taken more reformist positions, arguing against many of the rules that their culture promoted.

At the critical level, principles (maxims) do not need to be simple, as this level of thinking is not meant to be used on a daily basis. According to Hare, a moral statement evaluated at this level should refer to all morally relevant properties of the choice at issue. For example, a choice about whether to torture an informant to get him to provide information could depend on the probability that it would elicit information that could not otherwise be elicited, the probabilities that various numbers of lives could be saved with the information, the probability of harmful and lasting side-effects of the torture itself, and so on. To ask whether a property is morally relevant, ask whether it could potentially change the conclusion, even in a hypothetical situation.

By this criterion, and by virtue of Hare understanding moral judgments as universal, one property that is not morally relevant is the identity of those affected, or, more generally, anything we describe with a proper noun. Thus, if critical reflection yields the conclusion that torture is justified in a particular case, the judgment implies that the person drawing this conclusion should also be tortured if she is in the same situation as the informant in question. (This provides a significant constraint against oppression: presumably, few Nazis would have continued to prescribe the Holocaust, for example, even in the event that they were in the position of their victims.) Also irrelevant for Hare are the opinions of others about what is moral or immoral, unless they actually suffer from seeing their opinion violated.

Hare’s criterion of universality implies that the judgment must apply in both hypothetical and real cases. And it must consider all those affected since they are clearly of moral relevance. The critical thinking proposed by Hare thus requires us to engage in role taking, putting ourselves in the position of others: considering the effects of a choice on everyone and aggregating these effects on everyone’s preferences as if they were conflicting preferences within the thinker herself. Hare calls this a Golden Rule argument.

Hare notes that universal judgments made at the critical level can conflict with intuitive judgments. For instance, a person faced with an actual decision about torture may have a strong moral intuition that torture is never justified. Moreover, it may be better to follow this intuition rather than to try to think the case through at the critical level. The critical level is an idealization prone to errors, especially when the person’s reasoning is affected by (self-serving) cognitive biases. Yet, it is this critical thinking, properly done, that leads to conclusions that are consistent with utilitarianism.

Hare has thus begun with an analysis of what moral judgment is and concluded with a scheme that seems to lead to utilitarian conclusions at the critical level. But is Hare’s argument a “proof” of the normative status of utilitarianism? Utilitarianism certainly outperforms many alternative moral principles at the critical level. Various deontological principles, for instance, would be unlikely to survive critical reflection, such as the Catholic doctrine’s prohibition of abortion even when that is the only way to save a mother’s life and preserve her ability to have future children, and when the fetus will die anyway from natural causes.

Hare devotes considerable attention to the case of the “fanatic”, someone who endorses a universal principle that leads to a conclusion that he too should suffer greatly if the principle were followed and roles were switched. The fanatic might conclude, for example, that he should be burned at the stake if he were a heretic, a view that very few would endorse. Of course, the mere possibility of someone suffering is not sufficient in itself to make a prescription fanatical. It is quite sensible for you to endorse a policy of compulsory vaccination, for instance, knowing that the vaccine has very serious side effects for a tiny minority, with full knowledge that you could be one of those who suffer the side effects. You would still endorse the policy at the critical level because, considering yourself in each person’s position in turn, your desire to avoid occasional serious side-effects is outweighed by your desire to reap the health benefits of vaccination in the vast majority of cases.

The fanatic goes beyond this, insisting that he positively endorses being burned at the stake if he turns out to be himself a heretic, even without any countervailing benefits for others, and no matter how much his heretic-self would then object to this treatment. Hare argues that the fanatic is not thinking well, not sufficiently vividly imagining himself in the roles of all the others affected, including himself in the hypothetical situation of being burned as a heretic. But Hare’s argument stops there. It seems open to the fanatic to simply disregard the preferences he would have in the heretic’s position, and so continue to universally prescribe the burning of heretics. There may even be fanatics like this in real life, such as committed racists who endorse depriving Blacks of certain rights even in the event that they turned out to be Black themselves.

How serious is the fanatic’s challenge? From a practical perspective, perhaps not so serious. Suppose that we succeed in teaching the entire population about utilitarian thinking and its relevance to public policy, and we are so successful that utilitarian arguments dominate public debate. Would this eliminate political conflict? An interesting further question is to what extent even universal agreement with utilitarianism would resolve disputes in practical ethics. Whether in politics or in practical ethics, some disputes would likely remain since even in the absence of normative divisions there would still be empirical disagreements. Consequently, fanatics are not the only problem. Utilitarian thinking depends on beliefs about the empirical facts (as Hare often points out), beliefs that will differ as a function of all the factors that affect human development. And there may be no system of rationality that will ensure agreement about beliefs or even convergence on such agreement over time. So disagreement always remains possible. Still, in practice there does seem to be a growing consensus among utilitarians today regarding the most important practical implications of their theory.

Hare does not attempt to resolve every issue in utilitarianism. We are still left with questions about how we should deal with past and future preferences or, for applied purposes, how to measure utility and optimize outcomes for social policies. But his arguments for utilitarianism do not depend on the answers to such questions.

What Hare has given us is not a solution to the world’s problems but a set of powerful analyses of moral reasoning that we can use to criticize and improve our own reasoning and that of others. Hare himself has written a large variety of essays in which he applies these tools to particular problems such as those that arise in bioethics, politics, education and religion. This includes many of the usual hot button issues, such as controversies about abortion, which Hare approaches from a utilitarian perspective but never based simply on calculating total utility. Considered by Singer to be the founder of applied ethics, Hare regarded moral philosophy not as an exercise in academic analysis but as a set of tools to be used in the real world.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Representative Works of Richard M. Hare

- Hare, R. M. (1952). The Language of Morals. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1963). Freedom and Reason. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1981). Moral Thinking: Its Levels, Method, and Point. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1982), Ethical Theory and Utilitarianism, in Sen, A.; Williams, B. (eds.), Utilitarianism and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 22–38.

- Hare, R. M. (1989). Essays in Ethical Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1989). Essays on Political Morality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1992). Essays on Religion and Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hare, R. M. (1997). Sorting Out Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Resources on Richard M. Hare’s Life and Work

- Price, A. (2019). Richard Mervyn Hare. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.).

- Singer, P. (2002). R. M. Hare’s Achievements in Moral Philosophy. Utilitas, 14(3), 309-317.

- R. M. Hare resources page containing Hare’s writings, secondary literature, reviews, obituaries and a bibliography [archive]

Prominent Quotes of Richard M. Hare

- “The rules of moral reasoning are, basically, two, corresponding to the two features of moral judgment… When we are trying, in a concrete case, to decide what we ought to do, what we are looking for… is an action to which we can commit ourselves (prescriptively) but which we are at the same time prepared to accept as exemplifying a principle of action to be prescribed for others in like circumstances (universalizability)… [I]f we cannot universalize the principle, it cannot become an ‘ought’.”4

- “[W]hat the principle of utility requires of me is to do for each man affected by my actions what I wish were done for me in the hypothetical circumstances that I were in precisely his situation; and, if my actions affect more than one man… to do what I wish, all in all, to be done for me in the hypothetical circumstances that I occupied all their situations…”5

- “[In the bilateral case]… if I have full knowledge of the other person’s preferences, I shall myself have acquired preferences equal to his regarding what should be done to me were I in his situation; and these are the preferences which are now conflicting with my original prescription. So we have in effect not an interpersonal conflict of preferences or prescriptions, but an intrapersonal one; both of the conflicting preferences are mine… Multilateral cases now present less difficulty than at first appeared. For in them too the interpersonal conflicts… will reduce themselves, given full knowledge of the preferences of others, to intrapersonal ones.”6

- “It is said that the prescription to keep all black people in subjection is formally universal, and internally consistent, and so is not ruled out by the Categorical Imperative. But the point is: can somebody who has fully represented to himself the situation of black people who are kept in subjection go on willing that they should be so treated? For if he has fully represented this to himself, he will have formed a preference that he should not be so treated if he is a black person; and this is inconsistent with the universal form of the proposed maxim. There is of course the problem of the fanatical black-hater who is prepared to prescribe that the maxim should be followed even if he himself were a black person. I have discussed the case of this fanatic at length in my books… and I think I have shown that my theory can deal with him. At any rate the Kantian move can be used in arguments with ordinary non-fanatical people.”7

About the Author

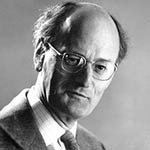

Jonathan Baron is a retired professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. His main research interest is moral judgment, particularly citizens’ judgments about public policy. He has published books and articles concerning utilitarianism and its applications, as well as psychology.

Singer, P. (2002). R. M. Hare’s Achievements in Moral Philosophy. Utilitas, 14(3): 309–317. ↩︎

Wittgenstein, L. (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. ↩︎

Foot, P. (1967). The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect. Oxford Review, no. 5. ↩︎

Freedom and Reason, pp. 89–90, 1963. ↩︎

Ethical Theory and Utilitarianism, p. 26, 1982. ↩︎

Moral Thinking, p. 110, 1981. ↩︎

Sorting Out Ethics, p. 135, 1997. ↩︎