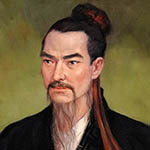

William Thompson (1775–1833) was a philosopher, political economist, and social reformer working during the early nineteenth century. He and his sometimes co-author Anna Doyle Wheeler made significant, though under-appreciated, contributions to the utilitarian, socialist, and feminist philosophical traditions.

1 Life

William Thompson was a landowner from Cork, Ireland with a reputation for eccentricity. He was often disparaged as “the Red Republican”—a reference to both the red flags of the Jacobins of the French Revolution and contemporaneous attempts at revolution against the British by the Irish Republicans.1 Besides his ideas and his sympathies for radical politics, Thompson’s atheism, vegetarianism, teetotaling, support of catholic emancipation in Ireland, and reductions of his tenants’ rent made him an outlier among the Anglo-Irish Protestants of Cork high-society.

As a social reformer, he had two primary goals: to improve the quality of and access to education for all and to establish worker co-operative communities. He agitated for people of all classes, including women, to receive a more extensive and useful education, rather than the poor quality, moralizing education that the working classes received in his day. Thompson drew up plans for the establishment of a school in Cork that would realize his vision for educational reform. Thompson’s school took inspiration from utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s own plans for a school. Thompson wrote to Bentham, seeking his opinion on his adaptation of the plan for Cork. Their correspondence resulted in Thompson staying with Bentham in London for five months, immediately prior to Thompson’s first published work of philosophy and political economy: An Inquiry into the Principle of the Distribution of Wealth Most Conducive to Human Happiness; applied to the Newly Proposed System of Voluntary Equality of Wealth(1824)—hereafter, “Inquiry”. In Inquiry, Thompson forwards a utilitarian critique of capitalism and sketches a de-centralized socialist alternative rooted in worker co-operative communities.

In the 1820’s, Thompson became a leading intellectual force within England’s burgeoning worker co-operative movement. He participated in debates defending the worker’s co-operative movement, contributed to its leading newsletter, and drew up proposals for implementing worker co-operative communities. The young John Stuart Mill, another prominent utilitarian philosopher, debated William Thompson at London’s Co-Operative Society. In Mill’s autobiography, he recounts: “the principal champion on their side was a very estimable man, with whom I was well acquainted, Mr. William Thompson, of Cork”.2 Mill said little else about Thompson in writing. However, Mill’s views of political economy, utilitarianism, and women’s rights evolved, to a certain degree, toward Thompson’s own. It remains unclear, however, the degree to which Thompson influenced Mill.

Besides Inquiry, Thompson co-authored with Anna Doyle Wheeler, Appeal of One Half of the Human Race, Women, Against the Pretensions of the Other Half, Men, to Retain Them in Political, and thence in Civil Domestic Slavery (1825)—hereafter, ‘Appeal’. Appeal forwards a utilitarian and socialist critique of patriarchy. It argues for not only the emancipation of women in the social, political, and legal realms, but also the economic emancipation of women from men. Returning to earlier themes in Inquiry, Thompson and Wheeler argue that education would be a vital part of such emancipation, since they believed that men’s control of knowledge was an important part of the subordination of women in society.

Upon his death, Thompson left a small portion of his estate to Anna Doyle Wheeler and the rest was to be used to establish a worker’s co-operative community. Thompson’s sister fought this, citing his plans for the worker’s co-operative community and his request that no religious ceremony occur at his funeral as evidence of Thompson having an unsound mind. The resulting court battles drained the estate of most of its worth and the worker’s co-operative community was never established.

2 Work

2.1 Social Science

Inquiry synthesized insights of utilitarian moral philosophy with the political economy of the day, especially Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Thompson called this synthesis “social science”. This appears to be the first known use of the phrase “social science” in English and predates Auguste Comte’s similar phrasing in French by several years. Thompson’s “social science”, because of its moral philosophical component, bears little resemblance, however, to Comte’s positivistic program for social science.

2.2 Bentham and the Reconciliation of Equality and Security

Thompson’s argument in Inquiry proceeds, first, by emphasizing that the utilitarian should care about how the products of the economy are distributed in addition to how to efficiently produce them. Second, Thompson follows Bentham in thinking that we should aim at “subordinate ends” rather than directly at the promotion of the most happiness for the most people. He focuses primarily on two of Bentham’s subordinate ends: security and equality. Security here means the security afforded by the recognition of property rights, including to oneself and one’s labor. When equality comes into conflict with security, Bentham recommended we give priority to promoting security. Thompson thought Bentham was working with an impoverished picture of human psychology and its connection to institutional contexts. One of Thompson’s guiding ideas in Inquiry is that we must attend more closely to the complexities of human psychology when following subordinate ends. This reveals problems with always giving priority to security. Given a richer picture of human psychology, security and equality are often deeply entangled. This is, in part, a matter of motivational pressures. For instance, inequality is discouraging: it creates envy. Envy, in turn, creates problems for the achievement of the other subordinate ends. Greater equality is thus necessary to ensure security.

However, the entanglement of security and equality was not only a contingent, practical issue for Thompson. It was also a moral one. Thompson uses the example of slavery to show that we must treat the security of individuals equally. It makes no moral sense to give priority to the security of the enslaver instead of treating the enslaved person as equal to the enslaver. Recognizing the security afforded by the enslaved person’s right over their body and labor is a way of treating them equally to others. And thus the explanation for why a utilitarian should oppose institutions of slavery reveals that equality cannot be ignored in favor of the security afforded by the recognition of status quo property rights. Thompson then extends this discussion to the inadequate compensation of wage labor, arguing that workers are denied the full product of their labor under a system of individual competition.

Thompson also argued for the importance of equality by arguing that equal relationships facilitate some kinds of pleasures that are more important than other kinds. He distinguishes several kinds of pleasures: physical, intellectual, social, and sympathetic. Chief among these pleasures are the social and sympathetic. They are derived from various feelings one has towards others, such as friends: love, admiration, respect, and so on. These pleasures are derived, at least in part, from interacting with others on voluntary terms. And equal social relationships, supported by equal security, are a precondition for such voluntariness.

Interestingly, Thompson claims that social and sympathetic pleasures are of a “higher order” than physical pleasures. While it is not completely clear what Thompson means, it is tempting to read him as offering a precursor to John Stuart Mill’s doctrine of higher and lower pleasures. Just as there’s disagreement about what Mill meant when he discussed higher and lower pleasure, so too there is room for disagreement about what exactly Thompson might have meant. Perhaps, for Thompson, social and sympathetic pleasures may just be of a greater intensity than physical pleasures. Or perhaps Thompson thought that even if the duration and intensity of a sympathetic pleasure was equal to the duration and intensity of a physical pleasure, sympathetic pleasures were more valuable. He never explicitly states which of these two doctrines he has in mind. He also suggests that social and sympathetic pleasures can often accompany and act in concert with physical pleasures—a good meal with genuine friends is more pleasurable than eating the same meal alone. This amplification would make the pursuit of social and sympathetic pleasures alongside physical pleasures of greater value than either pleasure pursued alone.

The conception of equality that emerges from Inquiry is complex. It is tied in various ways to the promotion of pleasure, the diffusion of knowledge in society, and the reduction of institutional subordination. For Thompson, little theorizing about the subordinate ends and their relation to the promotion of happiness can be done without attending to the details of human psychology and of the institutional arrangements in which we find ourselves. Thompson recognizes that there will be some conflicts between equality and security. And while he does not offer a comprehensive alternative to Bentham’s list of subordinate ends or an account of how to trade-off between them, he summarizes his recommendation as follows: We should give equality of security higher priority than the equality of the distribution of initial production. Equality of opportunity to acquire more through merit should take lesser priority than both other subordinate ends.

For Thompson, equality of security takes priority over enforcing status-quo security, e.g. in cases of slavery, the subordination of workers, and the subordination of women. However, it is unclear that Thompson believed that equality of security always takes priority over enforcing status-quo security. He may have allowed for some trade-offs between equality of security and the enforcement of status-quo security if it were obvious that the greatest happiness would be better promoted by enforcing status-quo security.

2.3 Marx and the Move from Equality to Socialism

Thompson did not use the term “socialism” to describe his position in Inquiry, and his work predates widespread use of both that term and of “capitalism”. However, he has been interpreted as a socialist more or less since the term’s widespread adoption because his critique of what he called “the system of individual competition” anticipated themes of later critiques of capitalism, particularly Karl Marx’s. Some make bold claims about the influence of Thompson on the socialist tradition of political thought, even accusing Marx of plagiarism—a point to be addressed in a moment.

Thompson believed that the best system for pursuing equal security along with the other subordinate ends of equality would be a de-centralized system of voluntary worker co-operative communities. These communities could share the initial product of their collective labor equally, allowing them to combat other forms of inequality, like inequalities among the sexes and in education, within their own community. And they could do so while maintaining reasonably high levels of economic productivity. Thompson thought his system would need to spring up organically from the voluntary and democratic agreement of workers and others already sympathetic to the workers’ cause. This belief put Thompson in disagreement with many of his contemporaries, who believed that violent revolution or courting rich donors were the best means of improving the plight of workers.

A central element of Thompson’s case for worker co-operative communities was a critique of the system of individual competition for economic production and distribution. For example, among Thompson’s chief complaints was that the system of individual competition did not distribute to workers the full product of their labor. Instead, owners of land, factories, and other capital would keep for themselves a disproportionate sum of the economic value produced by the labor of the workers (minus the material costs of production), which he terms “surplus value”. For Thompson, this feature of the system of individual competition was counterproductive to promoting the ends of equal security because it privileges the security of the owner of capital above all others.

Karl Marx’s theory of exploitation under capitalism appears remarkably similar to Thompson’s critique of the system of individual competition. Marx argued that workers in a capitalist system are exploited because those who own capital only have an incentive to employ a worker if doing so allows them to make a larger profit. The only way of deriving a larger profit from a worker is if some of the economic value produced by that worker (after the material costs of production have been accounted for)—which he also terms “surplus value”—is extracted by the owner of capital. The appearance of similarity is no accident: Marx cited Thompson occasionally and did so approvingly, despite his eventual distaste for other utilitarian thinkers, such as Bentham.3 The accusations of plagiarism stem, however, from Marx not citing Thompson in the first volume of his most important work, Capital. Anton Menger, an Austrian legal theorist, attempted to prove that Marx plagiarized his most important ideas from Thompson.4 This accusation prompted a response by Marx’s long-time collaborator, Friedrich Engels, co-authored with Karl Kautsky and titled, “Juridical Socialism.”5 (While they raise many compelling points, their reading of Thompson contained some inaccuracies.) Engels also, at least tacitly, responds to this worry in his introduction to the second volume of Capital, where he cites Thompson approvingly (the footnote further assesses Thompson’s influence on Marx).6

2.4 Wheeler and the Critique of Patriarchy

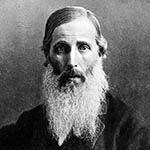

While Inquiry criticized the treatment of women in society, it was in Appeal that this critique was made in detail. William Thompson credits Anna Doyle Wheeler (1780–1848) with co-authoring Appeal. Wheeler was an early socialist advocate for women’s rights and equality both in speeches and in writing. It’s likely that she and Thompson met through their mutual acquaintance, Jeremy Bentham.

Thompson and Wheeler wrote Appeal in response to an article by utilitarian James Mill, father of John Stuart Mill. In that article, Mill argued that women did not need voting rights because their interests were already accounted for by their husbands’ and fathers’ right to vote.

Appeal is more than a sweeping indictment of Mill’s article. Thompson and Wheeler argue that there is no way to ensure equal security for women short of recognizing fully equal civil and political rights. This transformation includes suffrage, education, reforms to marriage, and, perhaps most radically, women’s rights to the full product of their labor. Thompson and Wheeler believed that equality for women would not be achieved unless there were changes to the economic system that recognized the contributions of their labor. This idea follows naturally from Thompson’s work in Inquiry and Thompson and Wheeler’s argument early in Appeal against the claim that the interests of men were identical to the interests of women. The resulting picture in Appeal is that the emancipation and true equality of women required large-scale systemic changes to the social, political, and economic order. Indeed, the societal changes envisioned in the Appeal exceed those found in the most famous reply to James Mill’s article: John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill’s The Subjection of Women.

How to Cite This Page

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Works of William Thompson

Appeal of one Half of the Human Race, Women, against the Pretensions of the other Half, Men, to Retain them in Political and thence in Civil and Domestic Slavery: in reply to a paragraph of Mr. Mill’s celebrated “Article on Government” (1825) co-authored with Anna Doyle Wheeler

Practical Directions for the Speedy and Economical Establishment of Communities on the Principles of Mutual Co-operation, United Possessions and Equality of Exertions and the Means of Enjoyments (1830)

Resources on William Thompson’s Life and Works

Dooley, D. (1996). Equality in Community: Sexual Equality in the Writings of William Thompson and Anna Doyle Wheeler. Cork University Press: Cork, Ireland.

Villanueva Gardner, C. (2015). Empowerment and Interconnectivity: Toward a Feminist History of Utilitarian Philosophy. Penn State University Press: University Park, Pennsylvania.

Kaswan, M. (2014). Happiness, Democracy, and the Cooperative Movement: The Radical Utilitarianism of William Thompson. State University of New York Press: Albany, New York.

Pankhurst, R. (1991). William Thompson: Pioneer Socialist. Pluto Press: Chicago, Illinois.

Prominent William Thompson Quotes

- “I conceive, then, that in order to make the noble discoveries of political economy… useful to social science… it is necessary always to keep in view the complicated nature of man… Without constant reference to it, the regulating principle of utility is sacrificed and… the indefinite increase of accumulations of wealth… become worthless objects consigning to the wretchedness of unrequited toil three-fourths or nine-tenths of the human race, that the remaining smaller portion may pine in indolence midst enjoyed profusion.”7

- “The direct operation of wealth is chiefly to afford the means of more extensive pleasures of the senses: it is only indirectly that it operates to increase our moral and intellectual pleasures; and when unequally distributed, and in very large masses, it tends, as will be proved, to eradicate almost entirely these higher moral and intellectual pleasures.”8

- “The only and the simple remedy for the evils arising from these almost universal institutions of the domestic slavery of one half the human race, is utterly to eradicate them. Give men and women equal civil and political rights.”9

About the Author

James Goodrich is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a member of UW-Madison’s interdisciplinary cluster in the ethics of computing, data, and information. He works primarily in normative ethics and the interdisciplinary field of philosophy, politics, and economics. In normative ethics, he works on the foundations of consequentialist moral theory and related issues in the ethics of harm. His work in philosophy, politics, and economics concerns the impact of various information technologies on market institutions and property regimes. He also has interests in nineteenth-century moral and political thought, especially in the utilitarian and socialist traditions.

For the most comprehensive overview of Thompson’s life and works, see Dooley, D. (1996). Equality in Community: Sexual Equality in the Writings of William Thompson and Anna Doyle Wheeler. Cork University Press, Cork Ireland. See also Pankhurst, R. (1991). William Thompson: Pioneer Socialist. Pluto Press, Chicago Il and Kaswan, M. (2014). Happiness, Democracy, and the Cooperative Movement: The Radical Utilitarianism of William Thompson, State University of New York Press, Albany NY. ↩︎

See e.g. Marx, K. (1847). The Poverty of Philosophy for citations of Thompson. ↩︎

Menger, A. (1899). The Right to the Whole Product of Labour: The Origin and Development of the Theory of Labour’s Claim to the Whole Product of Industry, trans. M. E. Tanner, Macmillan and Co., New York. ↩︎

Engels, F. and Kautsky, K. (1977). “Juridical Socialism”. Politics and Society, trans. Piers Beirne, 7(2): 203–220. ↩︎

What are we to make of Thompson’s influence on Marx? Given Marx’s citations of Thompson and use of Thompson’s phrase “surplus value” to explain a remarkably similar phenomenon, it’s hard to deny that Thompson had some influence on Marx. However, Menger’s accusation of plagiarism is unconvincing. First, the lack of citation in Capital should not impress contemporary readers. Citation practices at the time weren’t the same as they are now. Thompson could be accused of plagiarism for insufficient citations of Bentham, James Mills, and others by our contemporary standards. Second, the three volumes of Capital go well beyond Marx’s theory of exploitation, exploring a multitude of issues Thompson never discusses. Similarly, many of the concerns raised by Thompson in Inquiry are not addressed in Capital. Third, Thompson’s critique of the system of individual competition is thoroughly moral, rooted in his conception of social science as integrating utilitarianism with political economy. He did desire to make his critique more scientific than others, but he had no ambition to rid it of moral content. Marx’s theory of exploitation, however, was at least intended to lack moral content. And, fourth, there’s Thompson’s utilitarian reasoning itself. Inquiry is unmistakably shot-through with utilitarian reasoning. And, as previously mentioned, at the time of writing Capital, Marx had little sympathy for the utilitarian tradition, starting instead from his complex and original synthesis of Hegelian and materialist philosophy. That Marx was influenced to some degree by Thompson, as well as many others, seems undeniable; that this impugns Marx’s work in any way is specious. ↩︎

Inquiry ↩︎

Inquiry ↩︎

Inquiry ↩︎